The Shepshank Redemption

Exploring Britain's Most Haunted Prison

This is a free post, but should you be considering going paid, I’ve reduced my annual membership fees to half-price this week. In addition, if you subscribe before the end of Friday 5th October, you’ll receive a signed paperback of my novel Villager, wherever you happen to be in the world.

Mike touched my hair. I thought what had touched my hair was some furry dust that had gathered into a kind of dirt stalactite, which you often find hanging from the deep recessed window frames in the now disused prison at Shepton Mallet, but it was Mike. “Oh yeah, they are always touching my hair,” Emma, an employee of the prison for 18 years – for 12 of which it still contained inmates – would tell me later. By “they” she meant the ghosts, of which Shepton Mallet Prison has multitudes. When Mike touched my hair, I was having my first half-decent hair day after a run of bad ones, although I have no idea if this influenced Mike’s decision to be bold and make the first move. My friends Michelle and Sara and I were climbing the narrow, dark staircase up to the prison’s gatehouse at the time: a dank, claustrophobic space with a large hole in the floor that probably doesn’t even quite edge into the list of the top ten most atmospheric or terrifying parts of the building. Mike has been heard making his presence felt in here several times recently, by paranormal experts and ouija board owners, although nobody knows exactly who he is, or when he died. If you make a recording while you’re in the gatehouse you won’t hear him at the time, but you might on playback, if you slow it down. Sara, who hosts the tours here, has had her hair touched by him too.

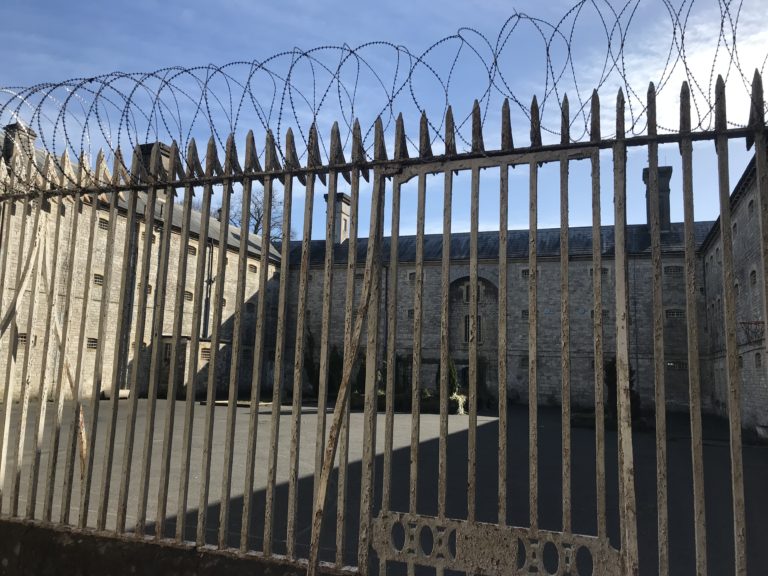

There are a few scattered bits of information and photos gathered by ghost hunters around Shepton Mallet Prison, plus a few historical recreations in the cells of C Block – the smartest of the penitentiary’s three sections of cells – but it could be argued that they are superfluous. The building speaks for itself. It’s the kind of place you suspect could be reduced to rubble, its foundations entirely rewilded, and would still radiate its dark history tangibly into the air. Before it closed, in 2013, it was the UK’s oldest working prison, dating from 1625. It was, in its latter years, a place for lifers: murderers, rapists, child murderers. It’s a building of quiet alcoves reeking of evil, sudden astonishing drops in temperature, half-revealed secrets. Across the road is a crypt for which the prison do not have a key. During construction work a few years ago, a sinkhole opened up between B Block and C Block, unveiling a horse skeleton. Seven executions by hanging took place at the prison between 1889 and 1926. “1926!” I found myself thinking. “That was pretty much last week.” If you are feeling a bit low about living in the era that you do, I’d recommend the perspective-enhancing properties of a visit here. The summer before last, on a country walk, I stole four corn on the cobs from a field. Had I done that in the 1700s and been caught, I could have easily ended up here, doomed to die of smallpox, picking apart rope with festering diseased hands – the one bright spark of my day an hour in the exercise yard with a bag on my head, forced to walk anti-clockwise, in an attempt to symbolically turn back time and erase the wrongs I had inflicted on society, with my clinical and vicious corn-stealing. For the first two hundred years of Shepton’s existence as a prison, the average life expectancy of an inmate was between three and four months.

When I was first looking into the possibility of moving to Somerset, Shepton was the town I was most frequently warned away from. I will admit this, on the side of the naysayers: it’s the hardest place to get a good cheese and onion pasty in the whole of the West Country. The one I finally found, after nearly an hour of searching, tasted of toes. It’s a town of frightening dogs, tyre warehouses and Babycham, except nobody drinks Babycham any more, so the Babycham has had to adapt and become cider. Shepton is like the civic equivalent of a pair of cargo pants: hugely unfashionable and not very aesthetically pleasing at first glace, but full of unexpected pockets, many of which contain interesting stuff. The architecture around the prison end of town is especially attractive, and I include the facility’s 70 foot-high walls in that. It was beautiful weather when I visited and, after passing a vast cider factory which used to be a Babycham factory, and telling a man searching for his lost pitbull that I hadn’t seen his lost pitbull, I rounded a corner and discovered spring under the disused railway viaduct, in a flurry of sharp blue sky, blackbirds, fresh running water and Forsythia. The weather was the kind where you can’t quite get away with just wearing a t-shirt, but a jumper is too much, but I forgot this fact very easily inside the prison and was glad of the padded high-vis jacket Sara loaned to me for the day. How fucking cold was this place in actual winter? Not that the prison’s cold is a cold that can be compared to outdoor cold. It’s a very different cold, that goes straight into your mind, via a steel rod up your spine. The chill was noticeably fiercer in some rooms than others, and all across the bottom level of B Block, which is haunted by the ghost of a woman wearing a wedding dress who died of a broken heart here after murdering her fiance. I couldn’t help but note how many of the supercold rooms correspond with a gruesome or eerie detail related to us by Sara. In a malignantly chilly cell, next-door to the former quarters of one of 1970s Britain’s most infamous child murderers, people have often seen an unknown man’s disembodied face in the mirror above the sink. I approached the mirror and risked a selfie. I didn’t see an extra face on the photo, but I did see my own. It looked terrifying, and not just in that way that most selfies are usually a bit terrifying. I did not recognise myself. I looked angry. I didn’t feel angry, at all. I had rarely, in fact, felt less angry in my life. The face was me and it wasn’t, at all. Confused and unsettled, I deleted the face, forever. That said, it might still be there, in the cell. Who knows.

You hear distant echoing sounds as you’re wandering around the vast spaces of the prison: footsteps on sturdy metal stairs, the clang of a door. They might be the sound of other visitors – less than a handful come through the doors in the three and a quarter hours we are there – or one of the two other employees on duty, or they might not. There are two ways to visit the prison now: you go on one of Sara’s ghost tours, or you explore freely in the daytime on your own. Sara is the perfect host for either the supernatural or the historical side: an impressive retainer of information who clearly loves her job and is able to pinpoint the deeply fascinating in the ostensibly banal. This is just one of four jobs she does (in addition to being a single mother) – the others being bar work, selling houses, and writing and performing stand-up comedy. She’s just the right balance of sceptical and intrigued as a commentator on the supernatural. Until recently, she drove a car with its own ghost, known to her as Dead Susan, who would enhance her life with small posthumous acts of kindness. When she and Michelle were last here and listening to one of the slowed-down recordings she had made in one of the cells, they could clearly hear a voice saying “Saaaaaaave meeeee” but when they put it back to normal speed, they realised it was just a recording of Michelle asking, “I wonder if any of them will say anything.” Sara said that none of the employees of the prison are ever in any rush to go home. The building has a strange power that locks you to the spot, while you simultaneously yearn to flee its mould-pocked walls, psychotic smells and impossible cold. It was not unknown for inmates here to commit suicide on the verge of their release. The last escape occurred in 1993, when three prisoners used knotted bedsheets to scale the walls. Two were recaptured very quickly near their old homes in Bristol. Another went directly for a pint in the Dusthole, the pub most local to the prison, where – upon drinking a second pint – he was recognised and apprehended by two prison guards who’d gone there for afterwork refreshment. Three years after this, toilets were finally added to cells, although many longer term inmates preferred to continue to defecate in newspaper, which they then threw into the yard, as tradition dictated.

By the time we were in C Block, the final segment of our visit, I was very keen to leave, feeling to an extent that I had been serving an actual sentence here and had a fresh appreciation of all of the life I had taken for granted, but strangely found myself not acting on this impulse. I stood rooted to the cold hard floor, imagining life here in the late 1930s, when the building was repurposed as an American Military Prison. During this period, C Block remained as English soil, housing various not insignificant historical documents, including the Domesday Book and The Magna Carta (rightly, nobody suspected Shepton would be high on Hitler’s “must-bomb” list). A man called Mr Johnson was tasked with looking after these, and his son – now in his 80s – recently revisited the prison. He recalled riding his tricycle around C Block, as gospel singing floated over from A and B Blocks. If that sounds quaint and idyllic, it is worth bearing in mind that 16 US soldiers were hanged here during the Second World War. 13 of the hangings were carried out by the famous Nottinghamshire-born executioner Thomas Pierrepoint, who legally killed a total of 294 people between 1906 and 1946, but was opposed to capital punishment and liked to farm in his spare time. The execution chamber and the drop room are not among the coldest places in Shepton Mallet Prison, but the corridor leading to them definitely is.

In a cell a laminated photo of a young GI was recently left anonymously, without explanation: a smiling, brightly toothsome face that could only have been American. You won’t find prisoner’s possessions in the cells, but the aura of recent occupation is palpable, in the mould and dirt and graffiti, in the small sections of coloured tiles that a few prisoners grouted in to make life more bearable. Old smells are still here. The morgue reeks of burning hair. An aroma of old perfume wafted through the bottom of the gatehouse as we reached it, just after Mike had stroked my hair. In B Block, three vast paintings, all by the same prisoner, still hang in the corridors. One shows a train puttering through classically English countryside. Another is a fantasy coastal scene: Tolkien and Cornish cliffs rolled into one. The third shows a woodland in spring, full of roe deer and bluebells, with a gypsy camp in the foreground: an unshackled, happy way of life. We studied the paintings more closely. In the fantasy coastal scene, two hanged figures, possibly armless, were visible on a bridge. In front of the bluebell wood, on a table, attended by gamblers, there was a red wine stain that seemed to coagulate, as it hit the floor, into thick congealed blood. A woman standing behind the gamblers you thought, from a distance, might be happily watching the game, in fact looks thoroughly anguished. Off to the left, a man is approaching, wielding what might be a machete but is probably a cudgel, and apparently looking for a way to use it.

This is a piece I wrote in 2019 which appeared in longer form in my book Ring The Hill. You can purchase it from Blackwells here, with free worldwide delivery. My most recent books are Villager and Notebook.