Talking To Art Garfunkel About Books On A Bridge In South West England

This is a free post, but should you be considering going paid, I’ve reduced my annual membership fees to half-price this week. In addition, if you subscribe before the end of Friday, you’ll receive a signed paperback of my novel Villager, wherever you happen to be in the world.

I got chatting to a Cornish charity worker who’d come to collect our washing machine and, after some practical dialogue about the washing machine’s condition and the gradient of the road, we naturally moved onto the subject of Simon & Garfunkel. The charity worker, whose name was Darren, said I should check out Bickleigh Bridge, in Devon, just south of Tiverton on the A396, because it had inspired the song ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’. “Are you serious?” I asked. “One hundred percent,” replied Darren. I told him it was a coincidence that he should mention it because the album of the same name had been the last record I had played before packing up my stereo for my house move, not for any ceremonial reason, just because I happened to see it in a box and remember it is an album I often neglect in favour of Simon & Garfunkel’s previous LP ‘Bookends’, pigeonholing it unfairly in my mind as a diluted swansong even though every time I have listened to it I’ve been pleasantly startled by its bangers-to-guff ratio. “Oh, that is a coincidence,” said Darren, not sounding like he actually thought it was a coincidence. “But anyway, apparently Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel were staying in a cottage nearby, then Paul Simon decided to write the song.”

Unable to contain myself, the following day I visited Bickleigh Bridge, and could definitely see some of what Simon was getting at in the lyrics: the water did look like it had a lot on its mind, especially after the dramatic flooding Devon had experienced the previous week, while the bridge, as a result of major rebuilding in 1809 in the wake of the wrecking of previous incarnations of it by by countless previous floods, looked very solidly horizontal and dependable. In West Country songwriting fact terms, this was almost as cool as the time I found out the band America had written ‘A Horse With No Name’ while staying in Puddletown in Dorset. Soon I got to thinking about Art Garfunkel and, as I invariably do when I think about Art Garfunkel, also got to thinking about Art Garfunkel’s book collection. Since June, 1968, when he was 26, Garfunkel has logged every book that he’s read: a diligent archivism I have been envious of ever since I first discovered it via his website in the early 2000s. “It is not fair,” I remember thinking on a cold East Anglian day, in early 2005, poised to turn 30. “I want to be 26, alive in America in the turbulent and mindblowingly creative summer of 1968, in the most successful male songwriting duo of all time, and assiduously keeping a note of all the reading I do. But it is too late now, because I am old, it’s raining, my harmonies are all off, and it’s the 21st Century, and everything is over.” Garfunkel had read quite a few of the same authors in his 20s that I had (James Thurber, George Orwell, Joan Didion, Philip Roth) and, looking at his list again now, I notice that our tastes are not dissimilar, albeit with Art’s being more classical-canonical-traditional. I am pleased to see, in his middle years, he read Light Years by James Salter and So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell and The Portable Dorothy Parker and Ragtime by EL Doctorow and On The Black Hill by Bruce Chatwin and The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers but disappointed to see that none of them are marked with an asterisk: his system for highlighting his favourites. Maybe he was very ill at the time? As you scan his list, you find yourself wanting to fill in corresponding information from other parts of his life. I spotted a four month bookless gap from September 1969, which also just happened to be the period when Simon & Garfunkel were recording the ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ LP, but in January 1970 a more telling explanation for the hiatus is offered: the next book he marks as read is Moby Dick.

Possibly the main thing I have noticed about life to this point is that it’s largely an ongoing process of saying to yourself “Bloody hell, I am old now” then looking back at that point and thinking “Bloody hell, I wish I’d realised back then that I was far less old than I thought I was.” I think this phenomenon provides the central explanation for why, in the last couple of decades, I’ve not quite mustered the commitment to keep an ongoing Garfunkel-style record of all the books I’ve read. I have been too perfectionist about it, permitted myself to be too irritated about not doing it back when I was “young” and first acquiring a reading addiction. “Oh, but the books are on the shelf, so what’s the point, anyway?” I would argue to myself. But that ignores the fact that I give away books that I’ve not enjoyed or only thought were “ok” and buy more books than I can ever read.

What you might call another coincidence which took place in the week before I talked to Darren the washing machine collector and visited Bickleigh Bridge was that my other half Ellie and I had cracked open a new notebook, in which we are determined to log every book we read. My hope is that the additional pressure of not letting someone else down might give me the discipline I have lacked in the past. No, it’s not perfect, but doing it at 48 seems an improvement on waiting to do it at, say, 58. I’ll still be able to look back in years to come and find out that in early autumn 2023 I read a collection of Alistair Cooke’s Letters From America, Japanese Inn by Oliver Statler, Gertrude Stein’s Blood On The Dining Room Floor, The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen, Stranger Than We Can Imagine by John Higgs and Swimming To Cambodia by Spalding Gray. Maybe it will prompt me to remember some other detail from the life that surrounded that reading, such as that it was the time we got rid of a washing machine and the lanes around our house were briefly underwater.

I have noticed a few changes in myself in the last few months, since taking measures to limit my social media use to the bare minimum. One is a growing awareness of what I have and what I have done so far in my life and a diminishing anxiety about what I don’t have and what I have not achieved. I used to get far more sad about all the books I hadn’t read and I am certain that Twitter - and, to a lesser extent, other less breakneck social networks - exacerbated that: not just because of all those people posting their towering piles of ‘Books I Have Read This Month’ but because of the high speed cultural box-ticking “What’s next?” outlook social media fosters. I still want to read as many great books as possible, and almost nothing makes me as excited as the prospect of reading great books, but when something - unpacking them and putting them back on shelves, for example - suddenly slaps me into a genuine awareness of how many great books I’ve already read, I realise I am no longer quite the ill-educated ne’er-do-well I once was. I probably read a few more per year, on average, than Art Garfunkel does. But it’s not a race and, if it was, I definitely wouldn’t be winning. I’m a slow reader and I’m at peace with that in a way I once wasn’t. What I’m less at peace with is the way the rushing chaos of digital existence has robbed us of physical mementos of the way we live. Keeping a handwritten list of books you’ve read might not do much to alter that but - like the dusting down of an old analogue camera or the filling of a notebook with thoughts - it’s a move in the right direction.

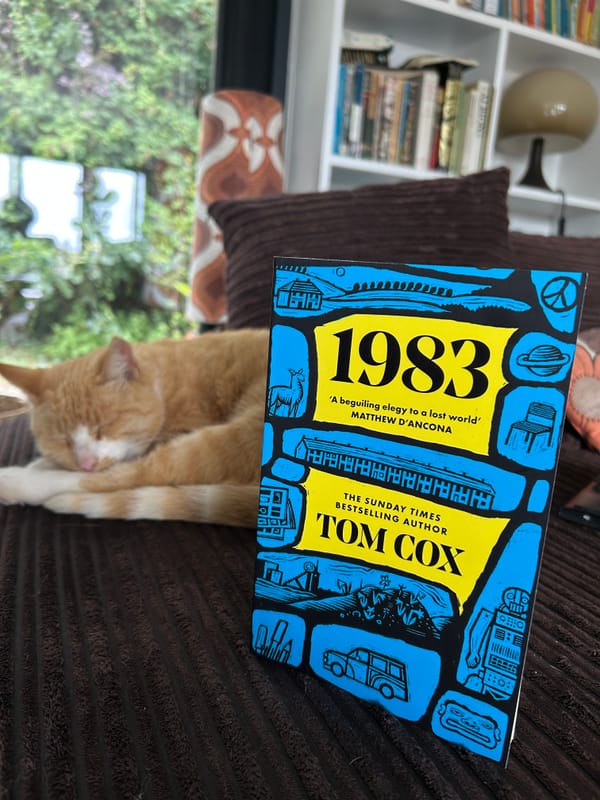

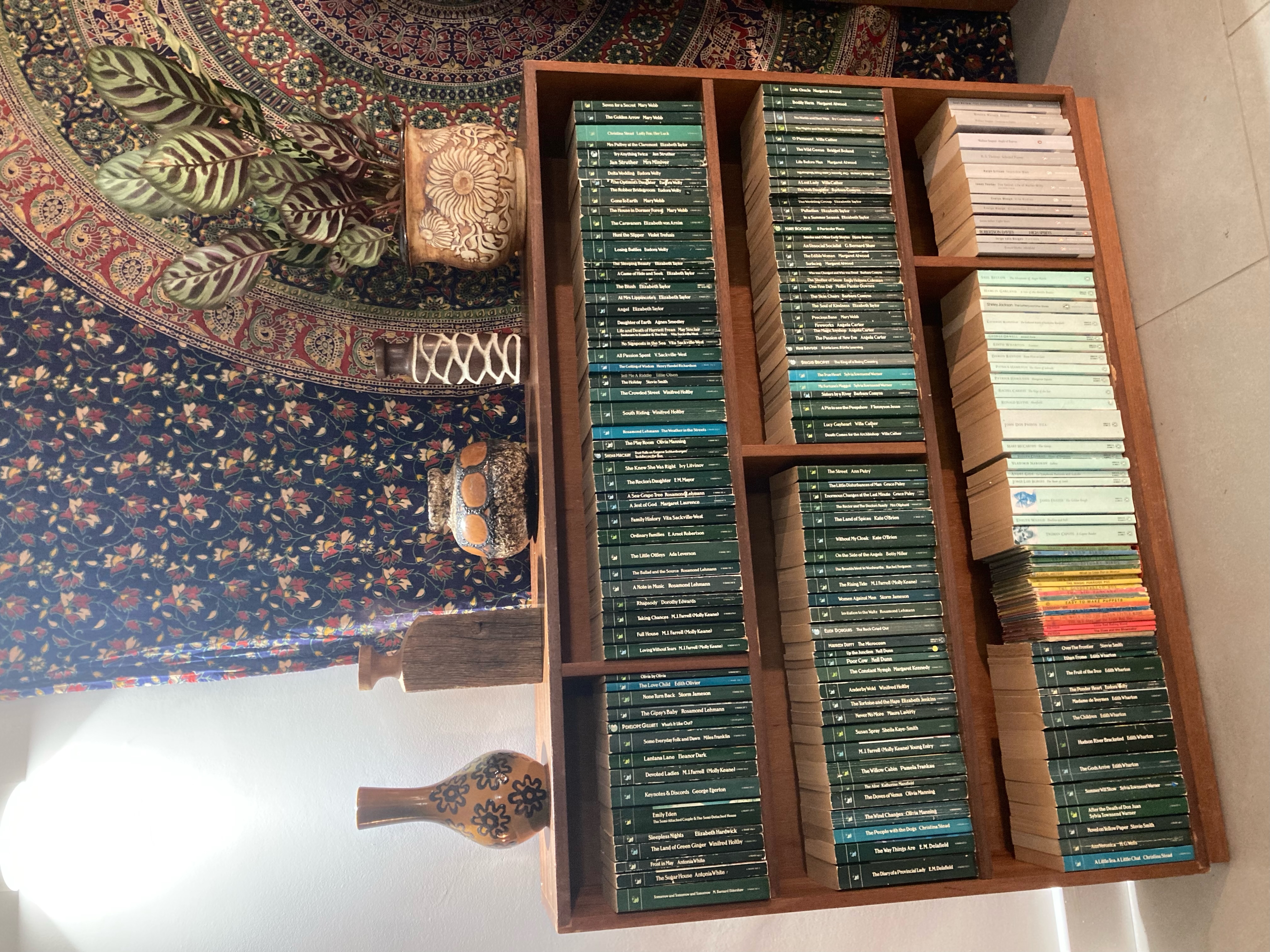

“Curate” has been a hideously overused word for at least half a decade but I’ve calmed my war against it lately. It’s used pretentiously in corporate brandspeak to a point beyond nausea but can be a very useful and accurate word. Have I curated the books I own? I am sure I have, in that I have a very specific and definite yet increasingly diverse idea about whose thoughts and from what period of history I want to shove into my brain, and my book collection is a representation of that (as overambitious as it might sometimes be) combined with a representation of what I have already loved shoving in there combined with my enthusiasm for (particularly mid 20th century) book design. I might have only read around half - probably under half - of the beautiful 1970s and 1980s Picadors and Viragos I’ve collected but to me that’s a good thing. It means there’s so much still to look forward to. After all, it’s not as if there’s some prize waiting at the end. If there is a prize, it’s an ongoing, fluid one. Namely: the process of experiencing the six main kinds of “holy fuck” I experience these days when I’m reading, which can be summarised as:

- Holy fuck, the world is massive and complex and full of more pain and beauty and sadness and wonder than I ever realised.

- Holy fuck, there are more brilliant minds out there than I ever realised.

- Holy fuck, everything is not as simple as I used to think, even when I was first starting to think “Holy fuck, everything is not as simple as I used to think.”

- Holy fuck, I would have shot my mouth off a lot less at many points in the past if I’d known all this.

- Holy fuck, we are all very insignificant, in the grand scheme of everything - especially me.

- Holy fuck, I strangely kind of get off on the growing, broadening awareness of that insignificance, and the way each successive book I read underlines and add nuance to it.

Some of us get through all these books, and where exactly, tangibly does it leave us? Reading widely and voraciously will have minimal, if any, impact on the average conversation we will conduct with a stranger during our day-to-day life. It is hard to construct an argument that reading a lot will make us happier, or make us a fundamentally better person than someone who doesn’t read a lot. I am not sure that I can provide any solid evidence that even a fragment of many books I’ve read - even some I’ve loved - are still there inside me. Ellie recently started talking to me about a significant moment in Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast Of Champions and I was disappointed to find that I had no recollection of it. I suppose that’s understandable: it’s almost 30 years since I read it. I believe it’s still an intrinsic part of me, in some obscure archeological way. That’s what I tell myself, anyway. It’s very possible that books are not making us any more intelligent; they’re just pushing other things out of our brains, including books we have read at an earlier point in our life. I do far more blatantly stupid things than I used to do when I’d read fewer books. My dad recently took his and my mum’s walking boots to a charity shop instead of the bag next to them which contained the actual paraphernalia she’d marked for charity. My mum said it happened because he’s 74. But it might actually be because he’s read a lot of books. I like the unpredictable stew books make in my brain: it’s a kind of chaos I enjoy, unlike digital chaos. But it’s a chaos that does perhaps mean it’s even more vital to log the reading of those books in a notebook.

Art Garfunkel hasn’t logged a read book on his website since May last year. I hope he’s ok. I get the sense from the more recent titles on there that his and my tastes have forked a little lately. But I like to think we could still have an interesting chat about our reading habits. If we did, I’d of course also ask him about Bickleigh Bridge. In an interview with BBC Devon a few years ago he denied the rumour that it was the inspiration for ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ and said the phrase came solely from a Baptist hymn. However, it should perhaps be remembered that Simon wrote some of ‘Homeward Bound’ in Widnes, and as the Visit Mid Devon website - who are understandably keen not to let the Bickleigh connection die - point out: “It’s possible that he intended more than one allusion” with the title. Also, how can you really trust the accuracy of Garfunkel’s memory, when he’s read 1332 books since 1968?