Remembering A Very Special Cat

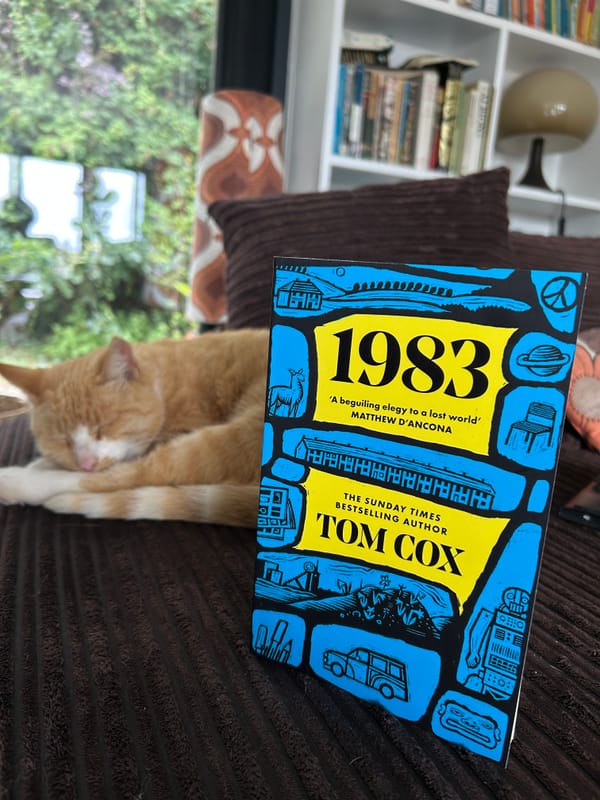

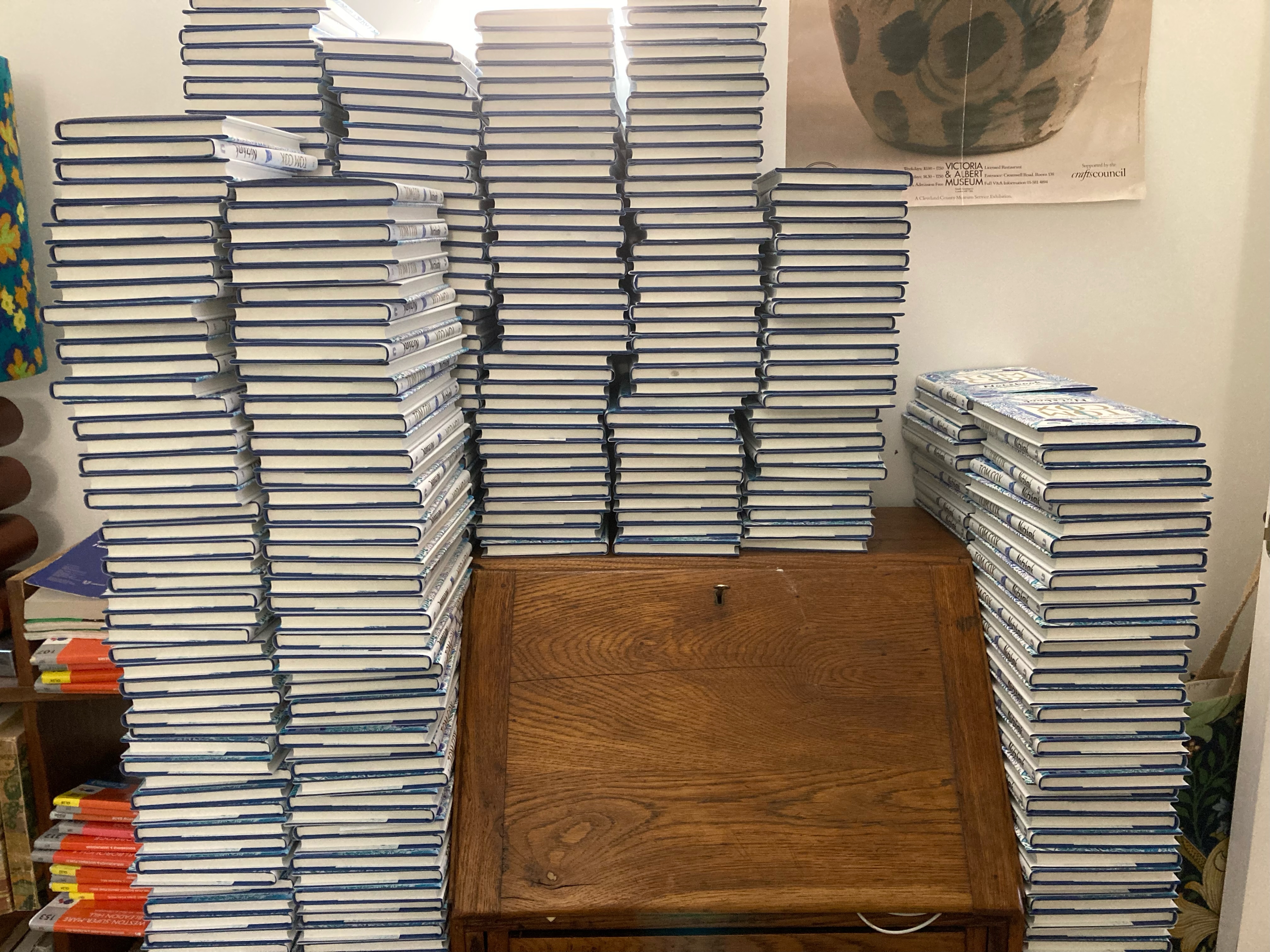

A fortnight ago I bought a lot of books from my publisher. What I am talking about here is “Level of books that take you several hours to shift into your house and stack, require the use of a wheelbarrow and leave you exhausted for 3-4 days afterwards.” Maybe I bought too many. Time will make that clearer. But my publishers offered me a fair deal on the last remaining hardbacks of both Villager (2022) and Notebook (2021), both of which are now widely available in paperback, and, because I poured years of my life into both, and believe in them - believe in books, generally, more than I believe in virtually anything else - I decided it would be worth making the effort to get them into the hands of as many people as possible. And by “people” I mean the right people: people who seem to be interested in what I write about, aka the exact people who have chosen to subscribe to this newsletter. “What is the best way to do this?” I’ve been wondering. Most of my subscribers here are outside the UK and international postage is expensive nowadays, especially when it comes to hardbacks. But also: I’m more keen on getting these books to appreciative homes around the world than making a profit from them, although if they did help me pay a couple of bills along the way, even better. Hence what I decided is this:

I’m taking 35% off the full subscription fee for my page until 10pm UK time on Tuesday 14th May. Everyone who signs up for that will receive signed hardbacks of Villager and Notebook AND (while stocks last) a small piece of original artwork by my mum, Jo. That means - even taking into account the cuts that Substack and Stripe take from each payment - my postage is covered on the books, wherever I send them in the world, and I make back the money I paid my publishers for them. And that is fine by me. (I’ll email you for mailing info once your subscription comes in.)

However, if you would like to give a little extra support for my writing here, you can choose the founder member option, which allows you to select the amount of money you pay per year (although I am not expecting or asking for this from anyone).

OR if you are in the UK and would like to purchase the books, signed, with normal UK postage, without taking out a subscription here, you can email me to arrange payment and delivery. They can also be purchased, unsigned, from Blackwells with free postage to most places worldwide.

I hope that all makes sense.

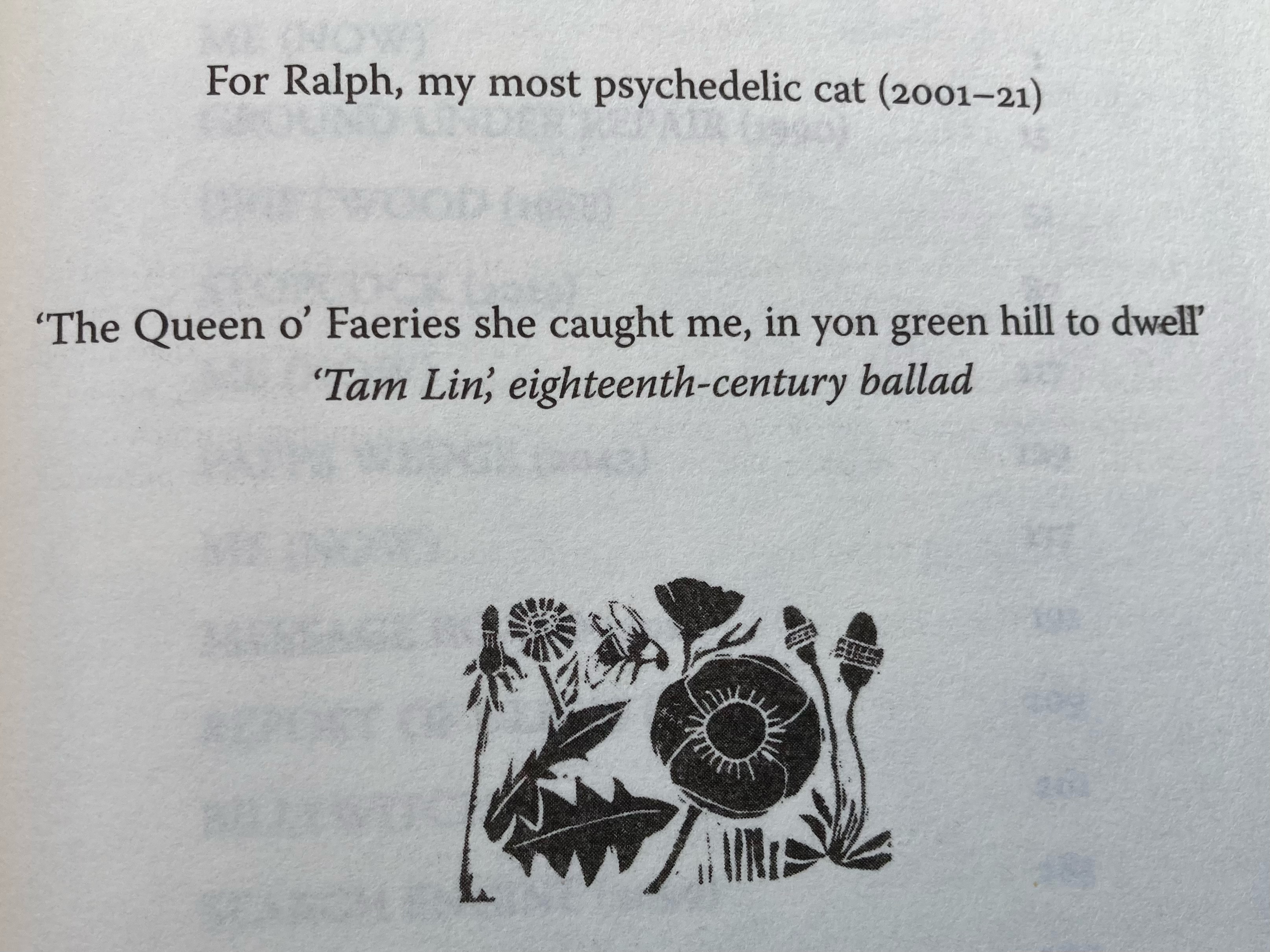

I thought, since I dedicated Villager to him, and it’s a beautifully bright morning here in Devon today, now would be an apt time to publish, for the first time on Substack, this essay I wrote about my sun god of a cat Ralph, as most of you won’t have previously read it. It’s here to read in full below, whether you are a paying subscriber or not.

Thanks so much for taking the time to open this newsletter.

Tom

Last Thursday was a scorchingly hot day and I decided it would be the day I would chop down the wisteria on the front of my house. I like wisteria but this particular wisteria was failing to fulfil what could be argued to be its two central duties as wisteria: flowering, and staying on the exterior of a building. According to my landlady, the wisteria had never turned the purple it was supposed to in the many years it had been there, and more recently it had decided to try to make its way into the house, which she had been understandably concerned about and asked me to attend to. When I got to the top of the ladder with my loppers, I noticed that, as well as entering the loft and gutters, several strands of wisteria had wrapped themselves around the internet, slowly attempting to strangle the internet and kill it. I could hardly blame the wisteria for this – the internet often feels like it’s doing more harm than good and a strong argument exists that it would be better for everyone if it was murdered – but I felt slightly ambivalent about the subject, so I gently began to release the internet from the wisteria’s grip and bring the wisteria to the ground. As I did, I found a nest containing three baby blackbirds. Not all the wisteria had been detached from the wall by this point, so I reclimbed the ladder and placed the nest in the most secure position I could, as close as possible to where it had originally been. I also covered it with various loose foliage, so the blackbird chicks were out of the fierce early afternoon sun. I fussed over the nest’s position for a long time. Half an hour. Probably more. I’m not sure. My grasp of time isn’t brilliant at the moment.

I don’t think I could have done anything more for the blackbirds, to try to keep them alive, and I am sure I would have done precisely the same thing in any other circumstances, yet somehow it seemed doubly important that I did keep them alive, extra crucial on this particular week that I was not to be personally responsible for their death. Four days earlier, my elderly cat Ralph had died. To be more accurate, four days earlier I had been responsible for the death of my elderly cat Ralph. Four days earlier, I had driven my cat Ralph to a one storey building a few miles from my house and paid a man to inject poison into his leg and end his life.

When you get two periods of extreme weather, one immediately after the other, it’s amazing how comprehensively the second period can vanquish the memory of the first period. Because of this fierce heat that I was trying to shield the blackbirds from, it was already easy to forget that only a few days before it had been unseasonably chilly and overwhelmingly damp here on Dartmoor. During the harrowing final four days of Ralph’s life, which I did my best to pretend weren’t harrowing, it rained almost non-stop. I’ve become accustomed to very old cats dying on me in the depths of winter, so, in cloud-darkened rooms, as it became increasingly apparent that Ralph was nearing the end of his life, I had briefly forgotten it wasn’t February and was actually the height of summer, very slightly over 20 years since Ralph’s birth. Just a couple of weeks before that, Ralph had been voluntarily sunning himself on the balcony outside my kitchen, and that had been wonderful to see, since he’d been such an indoor cat for the many months prior to that: an impossibly thin and frail cat who really did nothing more than sleep and lose control of his bowels and move creakingly between his food bowl and his litter tray. He had not been Ralph – not the full Ralph, not even quarter of Ralph – for a long time, but that brief bit of bathing in the power of those rays, that brief glimpse of his old sun god self, had made me think, “Yes, I am doing the right thing by keeping him alive, in this wretched state” although there had been many times in the preceding weeks when I’d questioned it.

Who was Ralph, back when he’d been totally Ralph? He was a rock star of a cat. A mellow alpha cat who never growled. A big strong cat with fantastic 1971 hair and sideburns who, when I anthropomorphised him as a Jim Morrison or Warren Beatty character with a string of illegitimate children scattered across the globe, I also liked to believe was secretly, deeply in touch with his feminine side. He was a cat who had the rare talent of being able to meow his own name – “Raaaaaaaaalllllph” – and, just like his brother Shipley, who died in February 2017, loved a good chat, and, also just like Shipley, seemed to need my company more than any other cat I’d ever known. He was, in his prime, a mouser, but not a birder: a cat who would have left those blackbirds alone. He was a cat who didn’t go out of his way to start rows with neighbours and foes but, if pushed, could settle one very easily with a large, solid paw. Until late 2016, people mistook him for a cat less than half his age. He was a miracle of vitality and still looked exceptionally youthful at 17, even though his bones had begun to creak a lot by then. I don’t know the exact date of his birth but, doing the maths from the moment I first met him in September 2001, I wouldn’t be surprised if it was Midsummer’s Day, and that would seem entirely fitting. Sun was very much Ralph’s thing. No cat has ever been better at locating a puddle of it to laze in, no cat has ever looked more blissed out and in his element with it shining down on him. It’s easy to start telling myself that this period of sun which we are having now could have given Ralph yet another extra lease of life, had he been able to experience it, but deep down I know it wouldn’t.

I began to write this piece about Ralph on the afternoon of his death but then I stopped myself. I’ve done it a few times now: written in celebration of the life of cats, in a flood of grief, and published that writing online only hours after their demise. I have done it because I feel a huge obligation to people who have never met them but grown fond of them via words on a page and photographs. It was something I never stopped to consider, fourteen years ago, when I decided to write some books that were kind of about my cats and kind of about lots of other things as well: that I had set myself up with a duty of public mourning, for years to come. What am I supposed to do? Just casually pop a photo of Ralph on social media in September, with a caption saying “Oh, by the way, my cat Ralph died a couple of months ago. Hope everyone is having a nice day!”? Or maybe just not mention him at all, kind of pretend he is still here? Not possible. I chose to write a series of books featuring Ralph and because of that I owe it to the people who came to love him through those books to tell them as soon as possible about his death. But I did decide to hold off, this time, just for a week or so, maybe not a fortnight, but enough time to live with it privately for a while. I decided I would selfishly limit my bereavement to myself, my family, and a few friends who knew Ralph in real life. I needed it, needed to go easy on myself: something I am not always very skilled at.

Even now, ten days on, I dread what the internet will do to this, how it will make it not about the real me or the real Ralph but the quasi me and quasi Ralph that best serve the internet’s goals. I dread the distracted deathlust of social media. I dread the people who are angry that I stopped writing books ostensibly about cats but who still obsess over Ralph and my one remaining living cat, Roscoe: people who are disappointed that I’m just a person who loves all animals and writes about many subjects and not the one-dimensional cat nut they want me to be, people who believe their disappointment negates the opinion of all the people who tell me all the time how much – and often how much more – they’ve loved the books I’ve written since the last one which was sort of about cats, many of which do still actually feature my cats, but aren’t cat books, which my cat books kind of weren’t anyway. I dread other people who will misinterpret that last sentence, not understand the full context of it, who have no concept of what has come at me online over the last few years, and think I’m being overly defensive. I have dreaded, as Ralph has wasted away in front of my eyes in the real world, the way that I can’t post on social media about one of the five books I’ve written in five years that I’ve worked my fucking arse off on without the very grounded-in-reality-and-experience fear of someone writing “Yes but how is Ralph?” or “More cats please” underneath it. I dread the way the algorithm will lap up this latest pet death of mine, however I handle it. And not any of that contradicts the fact that I massively appreciate the messages from people who do get it, that I also love several aspects of having cats who have been loved by strangers, or that I know the significance of Ralph’s role in my writing life. I just want to deal with this in the real world, not an online world that is skewed by addiction and the capitalist desires of robots. I want to deal with it in the world that realises that all deaths of beloved pets are crushing, not the world that concluded the death of my cat The Bear in December 2016 was innately more crushing than the death of my cat Shipley two months later purely because The Bear was “a more well-known internet figure”.

This is another thing I find hard about writing this: I am aware that the final section of my book Ring The Hill, which revolves in part around The Bear and Shipley, is one of the most cathartic and powerful experiences I’ve had as an author, and if this is less cathartic and powerful, to write and to read, it might seem that Ralph is somehow… less important. So I will say this: Ralph was not the cat of mine who lived longest – he didn’t quite make it to The Bear’s ancient 21 – but because I adopted him when he was a kitten, he is the cat I knew for the longest time. I have never felt closer to a cat, more part of a cat’s social life, than I did with him or Shipley. I won’t go into the details about his last few days, but it was very painful and very messy, and why wouldn’t it be? That’s what death is all about. I wanted him to die at home, peacefully, but we are lucky if that happens with an old, ill cat. The decision I made the Sunday before last – even though I am sure it was the right one – was harder than the one I had to make with Shipley, four and a half years earlier, appeared less clear cut, even though it was very clear cut. I am dealing with all the feelings I have felt before that don’t get any easier: the empty space in the house, the sense that I have heartlessly tidied a lifelong friend away. It’s fucking tough. I keep thinking about what else I could have done, and I’m sure there was something, even though there wasn’t.

I noticed, with great relief, a few hours after I’d put the blackbird nest back in the wisteria, that the blackbirds’ mum was returning to it, bringing worms and other treats. The relief was possibly even bigger, because I was aware that a couple of people on social media – probably only a tiny percentage of people, people who run on a technofucked tank of counterproductive rage – would undoubtedly be angry that I’d dislodged the blackbirds’ nest, even though they’d never met the blackbirds: people who probably assumed that I didn’t give a crud about the final bit of nesting season, and had been carelessly, wantonly chopping back foliage, shouting “BOLLOCKS TO ALL BIRDS, ESPECIALLY THE TINY BABY ONES!” The following afternoon, I looked again, and was amazed to see that the chicks were noticeably blacker and bigger: they were growing even more quickly than Ralph had shrunk during his final week on earth. Did a load of sun in the wake of a load of rain make blackbirds grow more quickly? Were they actually just like the dahlias in my garden? Two days later, I checked again and, miraculously, they had made it: flown the nest. I returned through the front door, half-expecting Ralph to jolt awake from his big cushion by the AGA, as I had every time I’d opened the door since Sunday. Roscoe was in the garden, rolling about with that look she’d had for the last few days: the look of someone who has finally got everything she’s ever wanted and isn’t quite sure what to do with it. The weather was glorious. I’d spent a lot of the last couple of days swimming in large natural expanses of water. My first novel was finished and almost edited. The friend who was visiting asked if I fancied a glass of wine. Life felt momentarily great, and I felt terrible about it. For more than a decade, there had been no point in my life when I was not caring for an ill or elderly cat. That’s a long, long time. Without that, life suddenly felt easier, simplified to a surprisingly large extent, tidier. And with the knowledge of this came a great rush of guilt for noticing it. But with it also came an epiphany of how hard it had been for so long, how painful it had been to watch my ancient companion suffer and just how much that had gradually placed a heavier weight on my heart, how amazing and unexpected it had been that he had even got through last winter, how lucky I’d been to have him so long, to live with this magnificent psychedelic rock messiah, this living god, this mellow work of art. Later that evening, I went out to water the plants and it felt like blackbirds were everywhere, diving ecstatically in and out of the hedgerows and singing some of their biggest hits. The evening light through the thick canopy was creating a selection of delicious sun puddles. I thought of Ralph, the joy he would have taken in selecting one of those to recline in, back only two or three years ago, when he had still been totally Ralph.

(July 21st, 2021)

Thank you for reading The Villager. This post is public so feel free to share it.