Owls, The Wire Man of Warleggan, Scarecrows and more...

Earlier this month a man called Chris sent me a photo of a wire figure nailed to a tree so I immediately asked him for map co-ordinates of its precise location. He said it was in Barleysplat Wood, which is on the steep rocky apron of Bodmin Moor, about half an hour from where I live. It was a busy afternoon, with lots of phone calls to make, packages to pack, Christmas presents to buy and writing to write so I immediately dropped all of it and drove to the village of Warleggan, then walked down a steep bridleway in the direction of the wood, which lies about a mile south. It was a place where you could really feel that way that, in the memorable words of my friend Becky, “the innards are closer to the surface in Cornwall than they are in other counties.” If Cornwall has a split personality – its frivolous, expensively dressed margins and its tougher, disgruntled interior – then you feel, in December, in a place like Warleggan, like you might be witnessing the most ghostly and lonely aspect of that second, often overlooked Cornwall, and that to do so is a special but not at all comforting kind of treat. While I was there I had a mooch around the grounds of the church, whose late vicar, FW Densham, was such a troublesome character that he alienated his entire congregation then continued to preach to an empty building, placing cardboard cut-outs in the pews. It’s said his ghost is still seen wandering the surrounding sunken lanes, almost seven decades after his death, but I didn’t see him, and, despite a very thorough search, found no evidence of the wire man either. A couple of days later, because these things are mysteriously important to me, I returned and looked even harder, again with no joy. A farmer called Charles, coming down the bridleway from the village on his quad bike, told me the Wire Man was definitely still there, “'bout half a mile away, just before you get to the funny lookin' 'ows” but by the time I’d got back to the foot of the hill, there was no sign, just before I got to the funny lookin' 'ows or anywhere else. I have talked a little more about this, amongst several other things, on my new podcast, which you can listen to here.

People know I like scarecrows and sometimes they tell me about village scarecrow festivals, but I’m rarely into what I see there. It always feels a bit like when there’s a band you love and they make a really great and weird album directly from their hearts and then another band turns up, and they’re signed to a major label, and sound like a more hygienic version of the band you love, and have almost certainly received and taken on board lots of advice from well-paid people in offices, and someone says, “Listen to these guys. They’re totally your thing!” It doesn’t matter how “horror” someone attempts to make a scarecrow at a village scarecrow festival, they are never as genuinely spooky and alive, in a dead way, as the ones you stumble on during walks: those which have been made, very creatively, with a minimum of raw material, by farmers and other countryfolk. It’s perhaps specifically that limitation of resources which is directly responsible for the level of genius on display: the folk art equivalent of a poverty-stricken juvenile Seve Ballesteros teaching himself to play every golf shot imaginable with just an old three-iron and the pebbles on a Spanish beach. It was around 2009 when I first started getting very interested in the secret zombie lives of these very basic scarecrows, which, either coincidentally or uncoincidentally, was also time when I was especially given to wearing old and threadbare clothes and first properly realised that bits of my body were beginning to fall apart and were likely to continue to do so for the remainder of my life. When I lived in Norfolk and regularly crossed the border for walks in the often-even-more-enchanting flatlands of Suffolk, I photographed dozens of them – vastly eclectic and inventive in their use of discarded coats and scarves and recycled agricultural containers - and it’s one of the things I miss about calling that part of the country home. Cornwall’s not quite such a rich hunting ground for the scarecrow enthusiast but I did find an impressively terrifying one guarding a bin bag at nightfall only a couple of miles from my house the other day: ambiguous gender, eyes partially hidden behind a ripped straw hat, biro-drawn teeth, stained (paint… spunk?) jogging bottoms. My phone died at the precise millisecond I tapped the button to photograph it and when I got home, the image wasn’t there, but I went back, as I always do in these situations, feeling even more compelled to do so after my disappointment vis-à-vis The Wire Man Of Barleysplat Wood. Second time around I got just the shot I wanted: several, in fact, as the pale Solstice sun lit the flecks of possible jism on the mawkin’s loungewear. I was talking recently with an acquaintance about potential epitaph, and I do not think “Never Less Than Tenacious In His Appreciation Of Strange Rural Mannequins” would be the most misleading, in my case.

Loosely speaking, the way publishing works is that you get a few books and authors that publishers, and the industry as a whole, gabble a lot about and really put some weight behind. Some of those books are very good, and some aren’t, but that’s not really the point. They’re big books, buzz books, and the sheer heft of coverage and chat about them makes them sell, at least for a while, although quite a few of them end up in charity shops, still unread, not long after that. Sometimes it can seem like these are the only books in the world, which is partly a function of that saturation, and partly a function of the fact that it’s probably easier to think of the planet of literature this way, because actually trying to comprehend how many books are out there – even how many books are published in the average week – makes your brain ache and prompts you to seek a quiet place to lie down. When you tell someone you’re a published author and they respond, “Oh really, would I have come across any of your work?” it is these books they are thinking about, and what the person asking you the question really means is “Are you one of those authors who get a huge marketing budget behind them and films made of their books and are constantly in people’s faces?” which is why I find the correct answer to the question is always “Definitely not”. READ THE REST OF THIS ON MY WEBSITE.

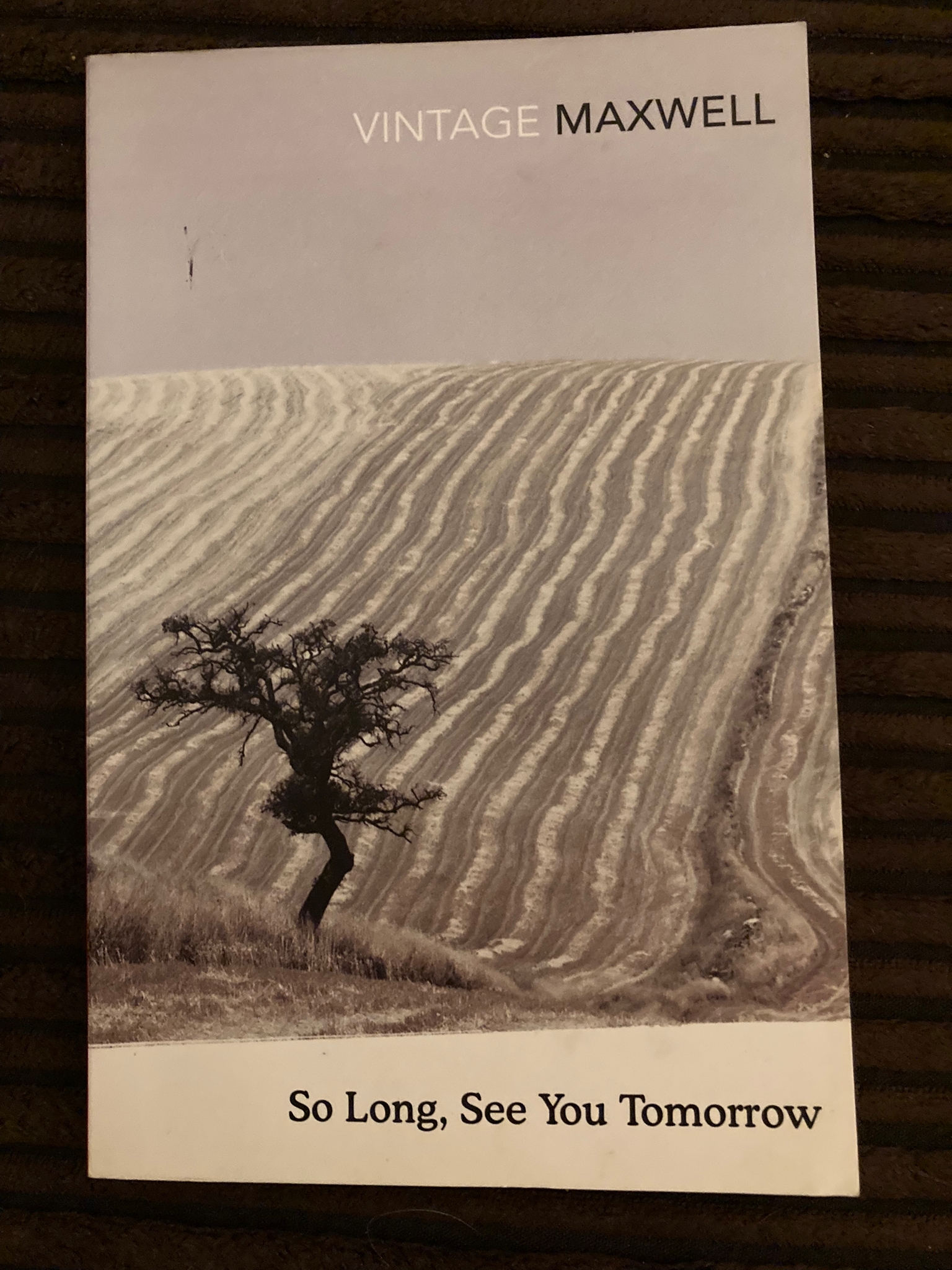

My book recommendation for this, my first ever newsletter, is So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell. As a slowish reader, I recently consumed this unique combination of memoir and fiction in marginally less than two days, pretty much everything else in my life being mandatorily pushed to one side as soon as I’d got to the end of the first chapter. What is it about? What Maxwell calls the “strange and unlikely things” that get “washed up on the shores of time”, for a start. Additionally: a crime of passion, tenant farming in the Midwest in the 1920s, two close male friendships severed in very different ways and the gossamer threads Maxwell - the former editor of Eudora Welty, John Updike and John Cheever - weaves between all of it, creating a powerful testament to a shared grief between himself and a person he had last set eyes on more than half a century earlier. The book had all the more impact for me as I read it directly after They Came Like Swallows, the similarly streamlined novel Maxwell wrote as a young man, which enabled me to reshape some autobiographical moments in the earlier book in my mind more poignantly and see the ways in which, in the space of four decades, a prodigiously sensitive and subtle writer had, towards the end of his life, become one of mesmerising nuance, capable of twisting you inside out emotionally with the the lightest of touches (I almost specified a particular scene here and told you to watch out for it, as it isn’t one for the emotionally fragile, but if I did, the appearance of it wouldn’t quite leave you as open-mouthed as it did me). It felt as magical as finding an old photograph album in a trunk that entirely reshapes a long-established personal history, and I doubt I’ll ever read anything quite like it again.

The last blushing clouds fell below the hill and owls came out in force, stronger than before. One sounded like it was in the bathroom. “Is there an owl in the bathroom?” I asked my girlfriend. “No, it’s just me,” she replied. “Are you sure?” I said. I’d had my suspicions for a while and this latest turn of events was doing nothing to put them to rest. I opened the back door, and the owl in question, clearly an experienced and comfortable ventriloquist, flew from the branch of a dead tree over my head. He was a male. I could tell. The signs were there in his very deep voice. His flight was kind of groovy, a dance, like some dude in a hip club, 1968 or maybe a little later, sidling up, checking you out, taking his time, getting plenty of evidence before making his move, which he would somehow shape into something that didn’t resemble a move at all. READ MORE ON MY WEBSITE.

Thank you for reading my first newsletter. As I mentioned, I also have a new podcast, which is a kind of companion piece to this, and was edited by Ellie McKechnie. With a little help from some friends, Ellie and I did make another podcast earlier this year, which was called Moorland Community Radio, and - unlike this one - was scripted and took place in a fictional moorland galaxy that could have been Dartmoor but wasn’t. It was essentially my attempt to make a more surreal and significantly sillier West Country answer to the 1954 Richard Burton reading of Under Milk Wood, mixed with a tiny bit of the second COB LP, and, as a universe, was supposed to get bigger and bigger, with me gradually learning to play guitar, balalaka and dulcimer as part of it, and eventually to relocate to outer space. But Under Milk Wood was made by the BBC and Richard Fucking Burton, not by two people with limited dramatic experience in a small room in Devon, and is just an LP, albeit a double one, and my priority right now is writing more books, and that, and regular website pieces, and house moves, is a bit much to all do at the same time. I always feel like I haven’t written enough books. There are so many more, fighting to get out, and it’s frustrating to know that some of them won’t make it. I am annoyed that I haven’t already written another novel since finishing Villager. However, it can’t be helped, and I’m very much on it now, and there will be some news about that very shortly, and I’m excited to tell you about it, but I will resist doing so just yet.

Happy Solstice to all, even though Substack is down so this will probably go out tomorrow now, so actually Happy Day After Solstice to all. The light is already beginning to return.

Tom