Nine Things I've Had On My Mind, Including Amsterdam

This week I’m offering 25% off all full annual subscriptions to this page. This will unlock access to my full archive of writing, along with all future paid posts..

- One thing on my mind recently has been the huge number of hardbacks of my books Villager and Notebook which I purchased from my publisher, at a lower price than usual, during their warehouse move, back in spring. There were over 3300 in total, which felt scarily massive, in terms of both space and outlay, but having done my best to relocate them in various creative ways (and today finding a little stash I’d forgotten about) I’m now down to the last 80 of Villager and the last 120 of Notebook, and, as part of a general reorganisation of my working space, would very much like to send them out to good homes this week. If you are in the UK and you’d like a package containing signed Villager and Notebook hardbacks solely for the price of postage (£5), please drop me an email via the contact form on my website and I’ll let you know how to pay (do check your junk while awaiting my reply). If you can give me a bit of money for the books themselves too, that’s really helpful, but it’s no problem if you can’t afford that/would prefer not to. I am also happy to send a package of three Notebooks for just £5 postage if anyone would like to pass them onto friends. (I’m sorry but I’m not extending these offers overseas right now as postage is much more expensive, and you would almost certainly find it less expensive to purchase from Blackwells, who do free delivery to many destinations.)

The cyclists in Amsterdam move like shoals of fish. You notice it more when, like us, you get an Air B&B in the suburbs and make your journeys into the city on foot during the commuter rush. As, in their hundreds, they glide down the neat clean tarmac paths towards the free ferries that will transport them to their jobs in the centre, you see an extraordinary spatial awareness at work and realise the cyclists are in fact one giant organism which, like the rest of the Dutch capital, functions astoundingly smoothly. Later, during our drive back towards the Channel through Flanders, we saw a murmuration of starlings in the sun-drained skies above the motorway, and that reminded us of the cyclists too. Suni, who took us on a ghost tour of the city on Halloween, advised us that the best way to stop them ploughing into you on the busiest streets is by making yourself into a chicken. He gave us a demonstration, pumping his elbows and pursing his beak. “Ok, now the spooky times begin!” he announced, leading us in the direction of the largest of the city’s two branches of UNIQLO. I noticed, before we reached the first destination on the night’s itinerary of haunted spots, that we had already lost the two burliest members of our party. “They said they wanted beer,” explained Suni. “Never mind! Ok, where we are now standing there were once lots of witches. Oh yes, many many witches. Or, as I call them, the strong ladies. They are around us now, even though you can’t see them. Oh yes.”

The ghost walk in Norwich, a few hours over the water to the west, used to be hosted by a driving instructor called The Man In Black, who took it over from a bloke called Ghostly Dave after Dave retired to open a rural pub. The Man In Black paid local actors to dress up as supernatural creatures and jump out at people, most memorably a skull-faced wolflike beast which, near Fire Bridge in 2011, one of my fellow ghost enthusiasts offered a tenner to, on the condition the skull-faced beast would “fuck off”. Suni’s tour of Amsterdam could hardly have been more different: he worked alone and dressed inconspicuously, with the exception of the bright red trousers he always wears to help his party locate him when he darts ahead into the herds of early evening tourists. He was originally a tour guide in his native India but fell for a Dutch lady and relocated to the Netherlands a few years ago. My suspicion is that ghosts are not his speciality and what we were actually seeing was a history tour that had been hastily “adapted” for spooky season. In terms of terror, the image from it that’s stayed with me strongest is an Ed Sheeran waxwork we passed, staring out at us from a window of the Amsterdam Madame Tussauds. But the architectural details we learned about the foundation of the city - the eleven million wooden poles it was built on, for example, after the damming of the Amstel - sent me down a historical Amsterdam rabbit hole that I still haven’t entirely emerged from, three weeks later.

Every time I tried to guess when a beautiful old building in Amsterdam was constructed, the answer invariably turned out to be much earlier than I’d imagined. In the first half of the 1600s, when we were still living in squat blobs of stone, Amsterdam’s builders were reaching boldly towards the sky with bricks of symmetrical beauty, constructing homes that might be viewed as man-made compensations for the chronic lack of hills, or even hillocks, in the area. The Dutch were stylistically ahead of the British then and they’re ahead of us now. Their restaurants often resemble calm, comfy living rooms, right down to the chilled out resident cats. Their shops have none of the fear of aesthetics that their equivalents in British cities tend towards. Their record shops contain better records for better prices. Everyone’s home seems to be full of houseplants and books and attractive lamps, completely eschewing the sterile, griege look in vogue over here. It was much the same in Antwerp, where we stopped for a night en route. If you’re talking about European excursions that do not centre around an assignment set by an editor, this constituted my 21st Century debut - my first non-UK holiday, in fact, for 26 years - and I have to confess I had been worried: worried about just how much it would trounce my memories of European travel from the 80s and 90s, of empty little French and Italian villages and original Fiat 500s and mindblowingly tasty roadside fruit, how much it would emphasise the corporate homogenisation of the planet. But it didn’t turn out quite like that. Yes, it provided another kind of confirmation of how cramped and digital everything has become. But it felt sophisticated, communal, open and untawdry in lots of ways that the urban Britain of 2024 is definitely not.

My one previous visit to Amsterdam had been in March, 1997: a short family holiday. Most people in the Netherlands were startlingly tall then, just as they are now, and I remember my dad telling me it was because when the dykes flooded hundreds of years ago none of the short people survived because they couldn’t keep their heads above the water. But mostly I remember my reduced psychic concept of Amsterdam’s layout, and a first pressing of the 1968 LP ‘Present Tense’ by Sagittarius I saw in a record shop for the equivalent in florins of £28, which I fatally dithered about buying (I’d never paid more than £15 for a record at the time) a few minutes before we were due to go home. Over the years, as the LP has skyrocketed in value, the incident has grown in dramatic importance in my mind and I talk about it like some other people might talk about, say, the time they almost got signed to Manchester United or were considered for Al Pacino’s role in Donnie Brasco. “Noooo!” I shout, in my memory, reaching one arm forlornly out, as my parents and girlfriend hustle me towards the train station and ‘Present Tense’ recedes into the background, destined for the hands of some other, less hesitant psych pop fan, for whom it will unlock a long life of easy, unadulterated magic.

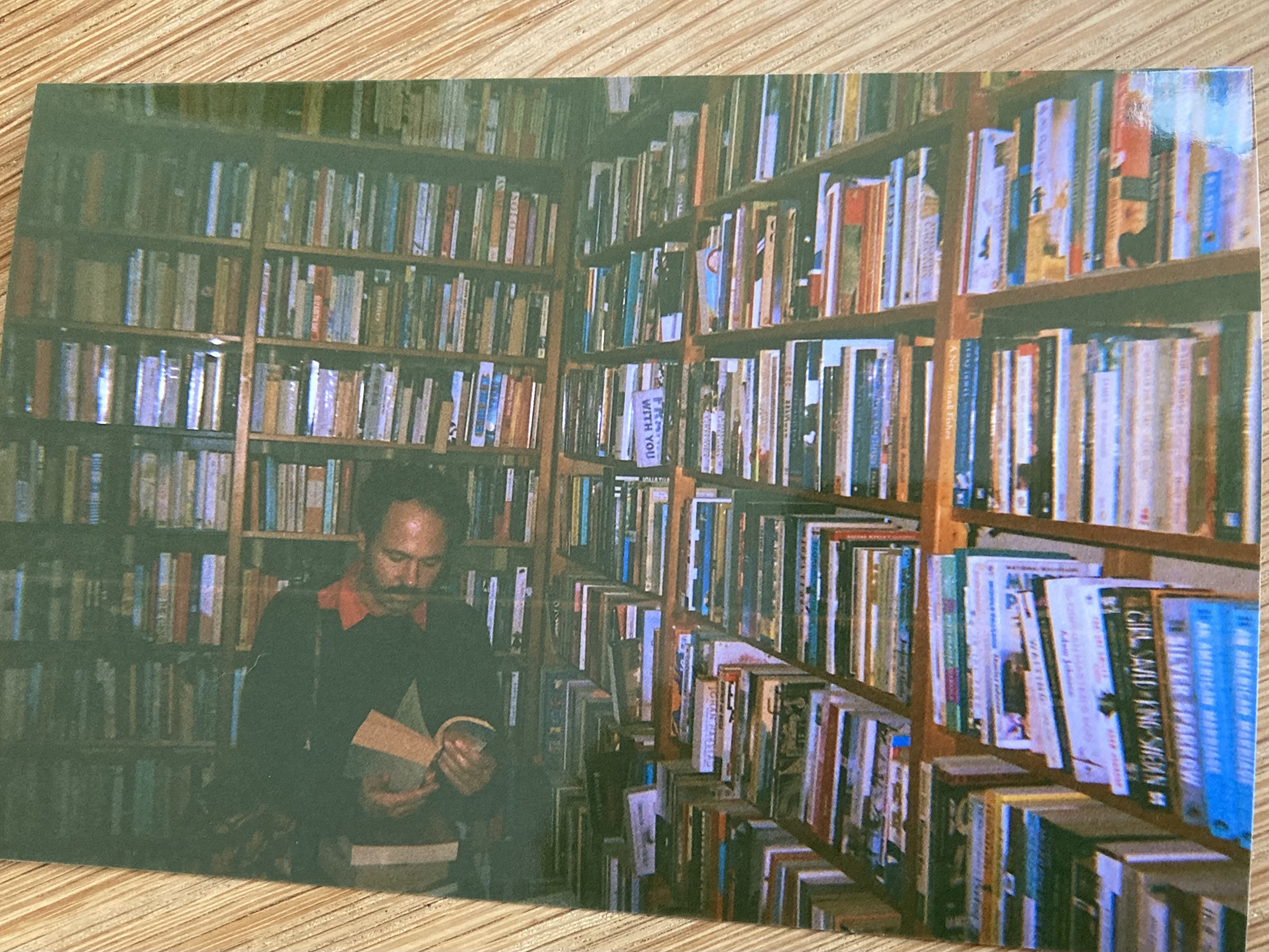

I’m more than twice the age I was then, feel - particularly in big cities - increasingly like a relic of a lost, more spacious era, but some things haven’t changed: I still can’t walk past a secondhand bookshop or record shop without going in, and persist in the belief that a great album can change my life, despite having nothing more than the most abstract proof to back it up. This time around in Amsterdam I bought - as well as saxophonist Archie Shepp’s career high point ‘Attica Blues’ and a hypnotic compilation of Lebanese folk music released by Philips in 1964 - a first pressing of ‘The American Metaphysical Circus’ by Joe Byrd And The Field Hippies and if I am not an altered version of myself just from hearing the bit where the chanting ‘Kalyani’ seamlessly segues into Christie Thompson singing “Waiting to die for the seventeeeeeeeenth time” on ‘You Can’t Ever Come Down’ I definitely do feel that, as a result, I have a broadened idea of how music can perform origami on your mind. I didn’t initially know it was Thompson singing, having assumed vocal duties had been handled by Dorothy Moskowitz, the singer from Byrd’s previous band The United States Of America. After I’d checked the facts, I got to wondering what Moskowitz had gone on to do after that utterly phenomenal band broke up. This led me to the discovery of Cracks, the haunting, animated short she voiced for Sesame Street In the year of my birth, which is all about a child watching shapes in the wall of her home come to life:

And that, in a roundabout way, got me thinking about the shape on my mum and dad’s kitchen ceiling that appeared in winter 2009 after their pipes cracked, which caused my mum to ask “Does this look rude to you?” and me to lie, in response, “No, not at all.”

After contributing to Sesame Street, making a jazz album in the late 70s and helping to inspire pretty much the entire career of the British band Broadcast, Moskowitz went on to become an elementary school teacher in California. It always fascinates me that these brilliant people, who have been involved in visionary records that nerds like me obsess over, are just, probably, to a lot of people who know them, somebody in a normal job who was once in some band or other which wasn’t quite good enough to be famous. This is a concept I touched on in Villager and had fun exploring more in my upcoming novel Everything Will Swallow You:

- Everything Will Swallow You has been fully edited and proofread now. I’m pondering the idea of serialising it here. That’s three novels, one collection of short stories and eleven non-fiction books behind me now and it feels like a line drawn: a more emphatic one than the one drawn after some of my other books were finished, although I can’t quite convey, or perhaps even pinpoint, why. So what next? I guess I will do some more writing since, when I’m not writing for too long, I start to feel like I’m missing a limb. My mind is still primarily on fiction. I plan to get back to short story writing, as it’s been too long and I think there’s much more I can do with the format than I did in Help The Witch (I plan to publish the results here). And as ever there are a couple of novels wrestling with each other in my mind to find out which one will see the light of day first. I also want to get back to learning guitar, catch up with the friends I’ve neglected while I’ve been working so intensively, and to take more photographs: proper photographs that don’t just exist on a screen. We took some in Amsterdam on the cheapest of cameras and, although they’re a bit dingy, there was something special about getting them developed and they make everything feel a bit more real. I suppose, in the end, I’m just like a lot of people who grew up in a simpler, more tangible age and feel a bit anxious right now every time they use their thumbprint to log into a screen: I want to change down a gear, dispense with the clutter, scale down, survive, but also broaden my mind and my experiences and make my life something I am more easily able to realistically measure and hold in my hand.

My latest novel, 1983, can be ordered from these places (amongst others):