Memories Of My Time Living In England In The Very Early Years Of The Century

RICHARD

I suppose it would have been around 2008. Certainly no earlier than 2006. The deepest part of a deep winter. Wind was blurring the air and thrashing every shred of extraneous debris from frightened trees and I walked, with no particular purpose, towards the dog-eared margin of the land. At a gap where a gate had stood in simpler times I paused to eat a jam sandwich I had found at the bottom of my rucksack. Raspberry. It was one my niece had made and packed for me the previous June, prior to a trip to the more welcoming original incarnation of Anita Roddick’s The Body Shop, but I didn’t mind: hunger and exposure to the elements had trounced the pedantic individual I had once been. It was then that I noticed I was being watched. The antlers didn’t fool me for a second. I knew it was my former work colleague, Richard Cruckshank, from so many years before. Some had called him my nemesis. I was never quite sure why. We’d never had much to say to each other and this afternoon was no different.

MY NAN’S RIDICULOUS VERTIGINOUS HOUSE

Sometimes all of the family would go to the house where my nan lived alone, which was very tall. That was fine by me but my sister Jean never gelled with the architecture. “Fucking stupid lanky wanker house,” she would spit, refusing to come inside with the rest of us. She’d wait in the garden in the crepuscular light while we were inside happily playing Backgammon or Scrabble beneath the glow of nan’s standard lamps, with their fringed, nicotine-stained shades “Is Jean still out on the lawn?” my mum would ask, every ten minutes or so. “Yes,” I’d reply, doing my best to mask my irritation at the repetition, in my patient way. “She’s staring furiously at the roof again as if exasperated by its unnecessary height.” But then one time I looked and she was no longer there. After asking around in the village, we ascertained that she had been carried off by one of the region’s few remaining wolves which, to our relief, returned her barely scathed to the lawn the following morning after what had evidently been a change of heart.

CAMPING

My mum despised all people outside of her bloodline and inner circle so whenever we went camping, which in those days was often, we always had to find a spot in some long grass, well away from the other tents. When we had selected a place that suited her, Paul would then very usefully cut down a patch of grass with one of his giant weird knives, making the tent less stressful to assemble. I was always asking Paul big existential questions, such as “Do you think nettles dream?” and “Why are the ears of bats so much prettier than ours?” which was probably very annoying, especially as I was 32 at the time. He’d never reply and would just sit with that wise soft look on his face and his beard smelling of the queue in the post office. In truth I’d forgotten all about him until recently when my parents and I were reminiscing. “Do you remember the time I couldn’t find the car keys and it turned out your friend Paul had hidden them in an owl’s nest?” my mum said. “He wasn’t my friend,” my dad replied. “I had never set eyes on him until that first time we set off for Somerset when I found him sitting on the back seat of the car, between the two children. I assumed he was somebody you’d met at work and become unusually close to.”

CHURCH

Just like now, in the very early years of the century religion definitely wasn’t for everyone, especially me, but sometimes, purely due to being irredeemably under her spell, I would follow my friend Winifred to church on a Sunday morning. Nobody else was ever there, a supercilious wind often danced up the nearby cliffs from the ocean, which was only seventy or eighty miles away, and the building was always very chilly, especially after vandals from the nearby town stole the doors and gave them away on the recently established website Freecycle. I’d wait, shivering, while she silently communicated with her Sleeping Pagan God, then we’d stroll gaily back down the hill, me pointing out facts I knew would charm her, such as that grasshoppers had existed for two hundred million years longer than grass, and she confessing her most idealistic hopes for the future, including her desire to one day meet and fall in love with a man with the physique of a state-of-the-art American fridge.

PETS

We were never the most assured family, when it came to pets, if I am honest. Each of my hamsters died in the car before we got them home from the place we’d rented them from and our one attempt to own a cat ended in disaster when, on a pit stop during a coach trip to Formby in Lancashire, it ran intently into a crowded service station food court, never to be heard from again. But we did have two witty and deeply loyal dogs, siblings. I forget their names now but I remember they loved nothing more than being submerged in water, so much so that this photo is the only half-decent one I still possess with their faces in full view. The reason the bigger brother on the right appears to be standing somewhat to attention is he has just heard the opening bars of the TV show Wonder Woman, starring Lynda Carter, which, at dinnertime, we deployed in the place of a more traditional call or whistle.

ANTI-MATERIALIST HORSE

There were two ways to get to the shopping precinct from home: the long way, via the main road, or the short way via the steep rocky track leading past Anderson’s farm, which, to my frustration, was often guarded by Old Mr Anderson’s dark-faced condemnatory horse. It was downright uncanny how often the big-nosed hairy twat was there. Did he not have important equine stuff to be getting on with? I talked the big talk in those days but always turned around when I saw him staring me down, usually not even making it to the shops, where I had hoped to spaff my meagre paycheque on a variety of scented candles, non-stick saucepans, asinine sloganed coffee mugs and equipment for sports I would probably never have got around to taking up. Of course, it is only now, with hindsight, that I realise my long-tailed tormentor had my best interests at heart and was, in fact, a considerate early anticipator of the more rampantly consumerist age that was to come, and the myriad problems it would bring, especially for those who, like me, were of a suggestible nature and inept at managing our own finances.

THE GREAT ROLLERCOASTER OF URBAN REGENERATION AND DECAY

Some of the old cities remained and were yet to be cordoned off. My favourite was Southampton, where majestic ships and car parks had once stood, but where now you could walk for hours, undisturbed, alone save for the company of maritime ghosts and opportunistic coastal badgers. I like how in the above photo of it you can discern both the remains of Borders Bookstore and of the original Colosseum. I never felt sad, meditating among its ruins, and rarely felt more in touch with the majestic, ceaseless circle of time.

LIGHTHOUSE

Of course, for most of this time I had been living in a lighthouse, which, thanks to sub prime mortgage lending, I had bought in 2002 for only £28,000, needing to spend only another £75 - mostly at Paperchase and Thorntons - to make it liveable. ‘Lighthouse Dude” they called me back then. I could get quite testy about it. “I’m not just my lighthouse,” I would protest. “I’m also a three dimensional human man, with a complex and frequently contradictory range of interests and personal aesthetics.” But I will level with you: I miss Lighthouse Dude. I miss the salty wind in his still-quite-thick hair. I miss the nights when filmically knowledgeable strangers would pull up and knock on the door, just on the off chance I happened to be the host of a local radio show, in the grip of an attack by supernatural forces. I miss the nights when the crew of fishing boats would come by and raid my fridge, even the nights when, having picked up sex workers in the ruins of Southampton, those same crews would gently turf me out of my own home, and I would shiver on top of the cliff, watching the waves and remembering my more romantic trips to church with Winnifred. This all being before the financial crash, when I sold the building for £15,000 less than I’d purchased it for, to pay off my debts, and moved into an unheated urban bedsit. But there is no productivity in dwelling on that. It was a different time, with different rules that cannot be transposed to today. I am just glad I can remember every second of it so unbelievably vividly.

Thank you for reading The Villager. This post is public so feel free to share it.

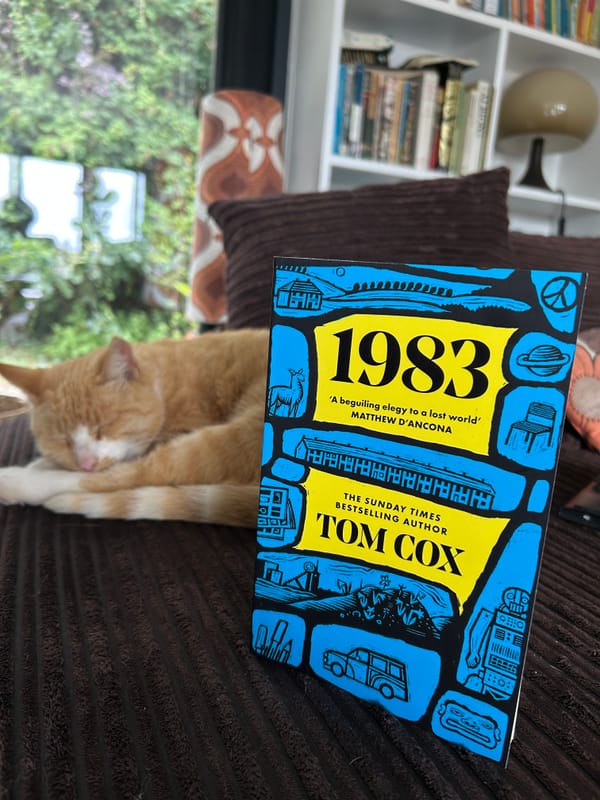

You can order my latest novel, with free worldwide delivery, here. Signed first edition hardbacks of my new novel, which is published in summer, can be ordered here.