Excerpts From My Notebooks

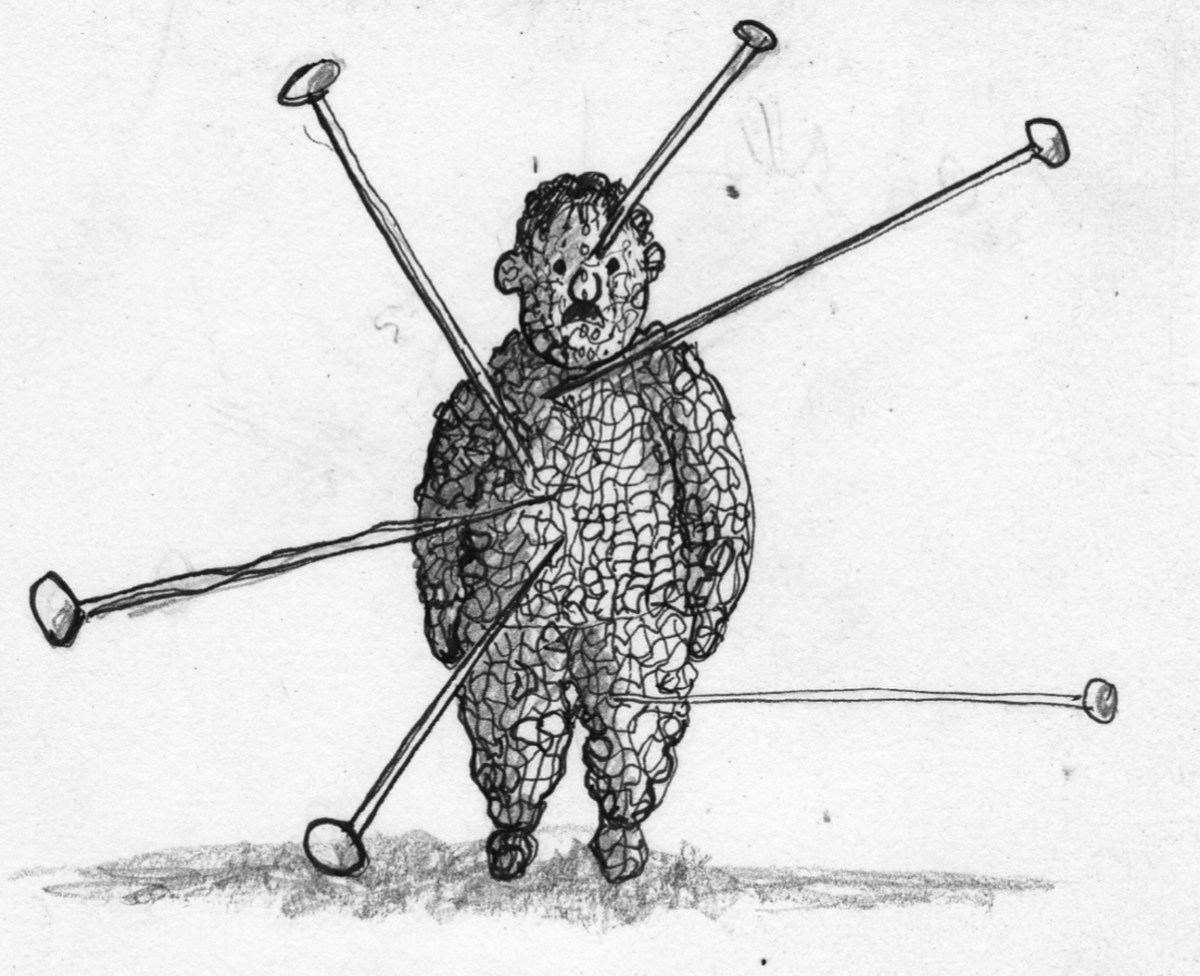

- A friend met me at the pub and told me he had been clearing out his gran’s house. One thing he’d found in the house was a knitted effigy of the man who had run off and abandoned my friend’s pregnant aunt. Into the effigy had been stuck twenty knitting needles: one for every year since the man had vanished.

- You can tell a lot about people from the way they act in a car park. People who reverse into a space in a car park tend to be people who like to forward plan very carefully. They book holidays and haircuts long in advance and never have empty tanks for their oil- fired central heating or run out of salt or non-bio washing liquid. I never reverse into a space in a car park.

- During 1997 my dad was on the phone a lot for work and I was too, and I was twenty-one and had gone back to live at home for a while, so I decided to get an extra phone-line in my bedroom, via which I could conduct interviews with American bands for newspapers and music magazines. As soon as the number was active, I received a call on it from a man asking if I could book him in for a haircut. I gave him the 9.25 slot, owing to the fact I’d had a cancellation.

- A lot of people think insects are out to make their life difficult but they’re not – they’re just being insects. Flying ants don’t live long, so while they do, it’s not fair to deny them their right to party.

- A solid cooking rule to follow is to remember that when recipes say ‘add two cloves of garlic’, it’s always a misprint and what they actually mean is six.

- I went to the pub with my parents. A waitress left her notepad and pen on the table and my dad immediately began to sketch a man sitting two tables away. My mum pointed out the trout on the menu and said it sounded nice and I said that I was full vegetarian now, not just pescatarian. ‘TROUT DON’T HAVE FEELINGS,’ said my dad. ‘THEY’VE PROVED IT.’

- It’s high summer in the South-west: calming and beatific in every way, with the exception of the panic of wanting to hold onto the moment, and knowing it will soon be slipping away. Last night I was at a party in a field, next to a house made entirely out of found objects. In Devon in July, there’s always a party in a field somewhere nearby, and it’s not hard to get an invite. A big fire. Lots of long rough-wool cardigans and productless hair. The moon was hanging full over the hedge and people were talking about it and how it was altering their mood, the friends who were acting crazy in the last couple of days because of it. A lady with a huge amount of hair took a seat next to me. She was barefoot but had a pair of socks in a wicker basket which she explained were ‘for later when it gets cold’. I was driving so I went to the bar and asked for a water. The man behind it – tanned, wiry, fiftyish, in a Bob Marley t-shirt – told me they didn’t have any. ‘But here’s an alternative,’ he said, handing me four ice cubes. ‘Hold these and wait five minutes.’

- A green woodpecker is on my lawn. It hasn’t seen me. It’s looking around, very cautiously, like somebody with very expensive clothes who knows they are elusive.

- Everyone was called John this month. It’s like that, some months. I had lunch with my friend John, who isn’t driving at present, after suffering a mysterious blackout and crashing his car into a wall in late summer. When he opened his eyes after the blackout, the front half of the car was dangling precariously over a twelve-foot precipice. ‘It was like the final scene in The Italian Job,’ he said. An elderly pedestrian, who had witnessed the crash, scuttled over and sat in the back seat, behind John and John’s wife Polly, to help even the weight out until the rescue team arrived. I sold some records to my friend John in Bristol and accompanied him to a screening of a documentary about drugs, which prompted me to read Aldous Huxley’s writing about drugs. My mum, visiting that week, told me about John, a family friend from Langley Mill in Derbyshire with a wrestling background, who recently witnessed a thug threatening a cafe owner in London with a knife, and calmly marched over and took the knife out of his hands. ‘I’ll tell you what knives are for: cutting bread,’ he told the thug, then sat down and resumed eating his chips.

- Ageing: the condition of becoming less serious about all you were once far too serious about and more serious about all that you once undervalued.

- The M5, southbound. The service stations zipped by: Sedgemoor, where one summer they had to open a second car park, due to its popularity. Taunton Deane, where I once burned my mouth on a pasty, then, seconds later, due to extreme hunger, forgot, and burned my mouth on the pasty again. There are some people you see at service stations that you don’t see in any other part of British life. Perhaps they live there? I’d been away from Devon for a while, living in a harsh place. Not that long, really, but it felt like longer, because it was winter, and because of that harshness. I saw the ‘Welcome to Devon’ sign then tasted a tear on my lip, before I’d even realised the tear had fallen from my eye. Moments before, I’d seen the Wellington Monument on the left side of my car, which always seemed to be surrounded by mist, and always made me feel better when it was on the left side of my car, rather than the right. I left again, somehow, due to a series of intricate circumstances. Then I came back. I couldn’t stop coming back. As I came back the latest time, and passed the monument, I mentally went over the stuff I might attach to the wall of a new house. There was scaffolding on the monument made it look like a giant rawl plug, up there in the mist on the hill.

- I walked to Porlock, on the north coast. Stories in my head, my feet writing them. Stories I couldn’t write if I stayed still. Deep in the woods above the waves: the tiny Culbone Church. A freshly dug mound of earth on the west side. Two local rival families are buried here, their graves facing one another. A cow once wandered into the church and pulled the bell and everyone who could hear it wondered who had died, which wasn’t many people, due to the lack of houses around.

- My friend Chloe, who lives in the Mendips, lost her hen. A neighbour telephoned to say the hen had been spotted at Wookey Hole, the subterranean tourist hotspot down the road, which, in addition to its world-famous caves and alleged witch, boasts such tourist attractions as a vintage penny arcade, an animatronic dinosaur valley and a pirate zap zone. By the time Chloe arrived, the hen had reached the crazy golf course, popularly known as Pirate Island. It was a busy bank holiday at the caves, and as Chloe chased the hen across the crazy golf course, lunging for the hen, and the hen repeatedly eluded her grasp, tourists attempted to get selfies with the hen. After much chasing between the holes – both those designed by nature, and those designed by the crazy golf course’s architects – with little help from the tourists, Chloe caught the hen, and returned it to her garden, where two weeks later it was devoured by a fox.

You can read more of these in my 2021 book Notebook, available here with free worldwide delivery from Blackwells. The above illustration of the voodoo knitting doll is by my dad, Mick (there are lots more illustrations in the book by him, and by my mum, Jo).

There are a few extra excerpts below for those who have been kind enough to sign up to this Substack page as paying subscribers…

- A man was ahead of me in the supermarket today, buying only two items: a miniature brandy and a pork pie. ‘Clive, do not fuck off down the wine aisle!’ said a woman to another man, a few yards away.

- In the cemetery, there were rabbits and a lone, pale ginger-haired boy and I noticed a cloth cap had been left hanging on one of the graves. The cemetery is wild and beautiful and was built to provide a new, non-denominational space in 1821, when the other cemeteries in the city were overflowing with corpses to the extent that body parts were often pushed back above the surface. People worried that the overcrowding was affecting the water supply, since most parish pumps were located next to cemeteries. The water from one Norwich pump was described as ‘almost pure essence of churchyard’. I moan about the water in modern Norfolk but I have found myself doing so less since regularly walking through the cemetery.

- Most bottled water tastes nothing like water. Volvic is in fact 96% steel. Then there’s Evian, which tastes like milk from an awful cottage.

- You’d think garden centres might be a celebration of life but vast parts of the ones near me are devoted to death: aisles and aisles of weedkillers and pesticides. Then there’s the gravel. So much gravel, of every different grade and shade any gravel enthusiast could possibly wish for. We have become a nation obsessed with gravel. It’s so prevalent that seeing a green driveway feels utterly evocative, an anachronistic shock. I love these unkempt emerald carports, the sprinkle of wildflowers you often find on them in spring, the way the grass will make its creeping escape from them and lick up the side of a nearby building.

- My parents are in Devon, staying at my house. I’m at their house, in Nottinghamshire. My mum calls to ask me how everything is. I tell her it’s fine. She’s in the car, which is being driven by my dad. ‘LET ME TALK TO HIM. I’VE GOT SOMETHING URGENT TO SAY,’ says my dad, in the background. ‘Hi,’ I say. ‘I JUST SAW A MAN SELLING CAULIFLOWER IN A FIELD,’ says my dad.

- I walked the Glastonbury site a week after the festival’s final curtain. It seemed even more vast than it did when it was full of people: a post-apocalyptic dust city, overrun with gulls. Dead badgers ringed its tarmac borders. I’m one of those unusual Outdoor People who is also Not Really a Festival Person, and I’d had misgivings about agreeing to talk on stage at the festival, having discovered its founder, Michael Eavis, was a supporter of the badger cull. Three days before the start of the festival, on a lane over two miles from the festival gates, my car was flagged down by an aggressive security guard, who, very reluctant to believe I lived nearby, told my friend Will and me about the serious terrorist threat faced by this year’s festival, and instructed us, ‘Believe me, you don’t want to see my face again, so I wouldn’t drive up here again in the next week, if I were you.’ For someone who claimed not to want us to be on this bit of road, she seemed inordinately keen to keep us on it for as long as possible, and, after the fifth or sixth sentence she’d begun with ‘I’m not being funny but...’ – the central hallmark of all people who are, in fact, being funny – it became clear that, for her, this was for the most part not about security, it was about pleasure: that particular kind taken when revelling in a small amount of power. In winter, I’d walked over the edge of the festival site, not realising that was where I was, and not seen another soul. Deer leapt out of long grass, shocked out of sleep by my incongruous presence. To see the area transformed into a temporary metropolis, so quickly, was dizzying and frightening. I stood on top of the southern hill on the Friday of the festival, looking at all those lights on the opposite side of the valley, as far away as a suburb is from a humming marketplace, yet still part of this same vast gathering we were attending. It made me think of the way real cities have been made, the way they bludgeon and transform the land, and what will be found beneath them when they have rotted away.

- ‘I HAVEN’T GOT A FORESKIN,’ shouts the teenager to his friend as he pisses into my hedge, piercing everything great the morning has offered.