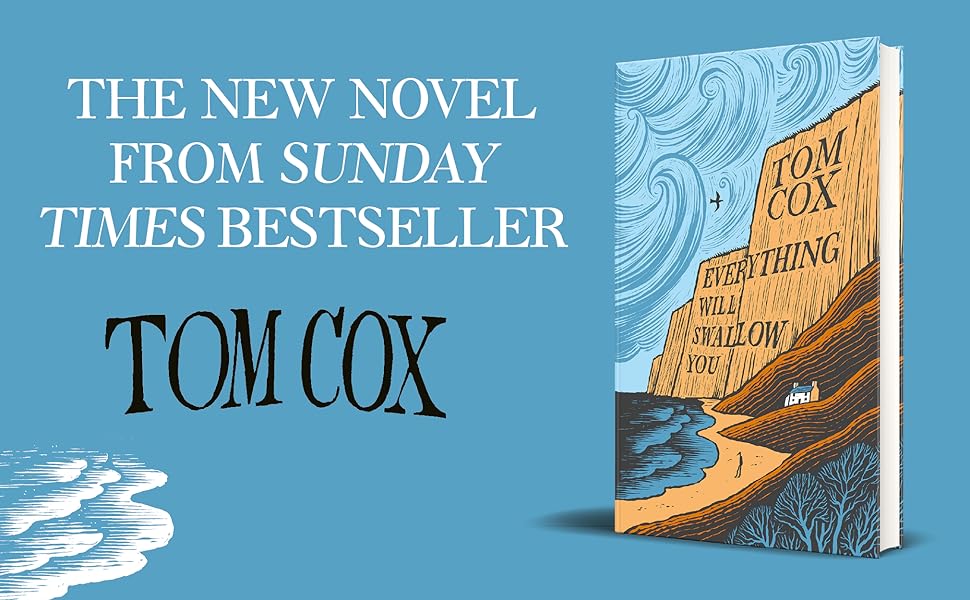

Everything Will Swallow You

EVERYTHING WILL SWALLOW YOU

Chapter One: The Reason Your Shampoo Wants You To Use More Shampoo Is Because That Means You Will Buy More Of Your Shampoo

The deer had been kicking the shit out of the hedgerows again. You could see their trail of destruction, curiously evenly spaced, all along the high ridge. ‘Bambi and the vegan diet are a clever bluff where deer are concerned,’ thought Eric. ‘They lull everyone into thinking they’re delicate peacenik flower children when in truth they’re punk anarchist mystics.’ This lot, here in west Dorset, would nut down fence-posts as if it were booting-out time on Friday night and the fence-posts had just called their sister a slag, sail through barbed wire like it was the mesh curtain over their gran’s back door and trash your delphiniums, never once pausing to tot up their fucks along the way. Over in the big field where the farmer particularly didn’t want them to go and a triangle of spidery dying elms looked like the marker posts of some oncoming dark ritual, they’d pop up from their hiding places in the cabbage in threes, gallop silently away, then freeze and stare back with a synchronicity that appeared choreographed.

‘They’re checking you out, pal,’ Eric told Carl. ‘Fellow oracles. Intimidated by your power.’

‘I was thinking we could try that new Indian in Axminster tonight,’ said Carl. ‘I fancy a break from cooking. I think I’m leaning towards a dhansak.’

‘Iggy Pop has deer energy, I reckon. Like one of those whatdcharmacall them, the little ones. Muntjac. The way he used to run around the stage. Or maybe he’s more like a bantam rooster, darting up to everyone with his chest puffed out, always legging it about in those little circles. Did I tell you about the one my neighbours had when I lived in Wales? Right little hooligan, he was. There was no hedge between the gardens so he’d be around a lot. The prick would come at me, claws flying all over the shop, every time I turned away from him. I’d be always walking about with all these cuts on the back of my legs.’

‘Dhansak is a curious one. The takeaways never seem to come to an agreement on the spice level. I’ve had some with quite a kick to them – nothing that I couldn’t handle, obviously, but the kind that would have someone of your inferior constitution blowing your nose every six seconds – but I’ve had some pitifully weedy ones, too. I see Iggy more as a centaur, myself. The bare chest and that feeling you get that he might have a couple of possible extra legs that he could whip out in moments of crisis. Hold on. Did you hear that? Over there. Was that a dog? It sounded a lot like a dog.’

The day, bracingly cold, chasing away weeks of pissant winds and concerningly lukewarm rain blasts, was one of those where a sun halfway up the sky will hold the landscape frozen in perfection for a number of hours, offering a bittersweet illusion of permanence. Dorset was a painting, balanced in the admiring hands of Horus. Where the busy little rivers had leaked, the ice, splintered by bootsteps, resembled the kind of glass you might find on the floor of an abandoned pub, but under the vandalised hedgerows it remained shadowed and solid. Soon it would begin to spread again and the Marshwood Vale would be drained of comfort, burping and groaning with the part-explicable sounds of the greedy January night. The transition was something Carl could already sniff on the ground directly in front of his nose. Looking at his only timepiece, which was now falling fast over the cliffs three miles to the south, it struck him that, as usual, they were going to be late. Eric had agreed to call at the Meat Tree’s house – which was around half an hour’s drive from where Eric had parked the van – to pick up the keys to the manor at five. The Meat Tree had emphasised that he had to go out by six at the absolute latest. It was now at least a quarter past four, and where was the van parked? Two miles away? More?

‘Here,’ Carl thought, ‘is one of the drawbacks of going out on walks with a collector.’ The impulse that made Eric feel the need to own nineteen Linda Ronstadt albums, including several from after the mid-seventies, when she began to go off the boil, was that same one which, half an hour before, had made him insist on following a footpath purely because it was one of the dwindling number in the Vale that he and Carl had not previously ticked off their list. It certainly could not be described as a bad footpath. Whether it was a necessary footpath, however, was highly debatable. And now here they were, a mile on from its source, ducking away from a potential Border Collie Situation through a hole in the hedge made by insurrectionary deer, onto an unmarked path beneath the steep brim of an Iron Age hill fort, in the direction of who knew what.

‘I’ve got a lot of trust in deer, me,’ said Eric. ‘What you’ve got to remember is that every place you walk, every one of these routes that some guy in an office decided to stick a sign on saying ‘Bridleway’ or ‘Public Footpath’, was originally made by deer, long ago. They know where they’re going and they know the best way to get there.’

‘I do completely see that,’ said Carl. ‘But at the same time we have no way of knowing where the particular pre-Christian deer who originally made this path were going. My guess is that it probably wasn’t a Victorian terrace on the outskirts of Sidmouth owned by a book dealer, nor a haphazardly parked vehicle waiting to take them to it.’

‘Cheeky fucker. That was some top parking.’

‘You left it sticking half out into the lane, looking like a stolen vehicle somebody abandoned before fleeing into dense woodland to evade the police. I’ll be impressed if it’s even still drivable by the time we get back.’

What would you have thought, if you’d been relaxing in the grass behind a hedge – a dense one, as yet unwrecked by a nihilistic buck or doe – and heard the conversation of Eric and Carl, from their unseen position on the other side of the brown-green divide? Would you have pictured, in your mind’s eye, a long-married homosexual couple? Two rivalrous professors of philosophy or zoology out for a stroll: one unlikely, a rough and ready maverick motormouth, the other more housebroken and genteel? A man still assimilating after arriving from the extensive and unknowable lands of the north, and his well-spoken friend from . . . another country, somewhere that you couldn’t quite pinpoint? Had there been a space in the bottom of the hedge, and had you spied, through it, two booted feet accompanied by four furry ones, you might have wondered where along the path the missing biped was speaking from, or perhaps just thought, ‘Oh, that’s sweet: the talkative man and his erudite migrant lover have a pet whippet.’ Whatever the case, it is extremely unlikely that you would have correctly guessed what was there, hidden from you by the tightly knotted twigs and branches.

The union of Eric and Carl Inskip was one that would not have been easily anticipated by society but, like any couple who’d been cohabiting for close to two decades, they were not unprone to sarcastic bickering. If somebody had witnessed this bickering – which Eric and Carl took careful measures to ensure almost nobody ever did – they might have observed that, more often than not, it was Eric who played the role of bickeree. The ways in which Eric had infuriated Carl, in the almost nineteen years they had known each other, were so numerous as to be unlistable but, even at his most exasperated – even at the height of his infuriation with Eric’s tardiness, his forgetfulness, his sticky-handedness, his repeated failure to close the door while urinating in the downstairs toilet, his general way of progressing through life like a boulder pinballing down a tiered forest chasm – Carl repeatedly found disarmament in Eric’s endearing way of never speaking to him as someone outside his realm of being, never as a lesser or something other, but in the casual manner that you would speak to a close, trusted long-time friend. In short – and, as he thought this, he suspected that at least one ex-lover might refute it – if you ever happened to be mad at the guy, he somehow made it impossible for you to stay that way for a length of time that would significantly erode your relationship.

As they rounded the base of the hill fort, an abrasive choir of voices could be heard directly below them: a quacking conference, with no space for one authoritative voice to raise above the din and call for order. Through the gaps in the trees could be seen a sloping field where, on a large patch of ice, 200 or more ducks had gathered, apparently for no reason other than to discuss what was most pressingly on their minds.

‘Ah, man, I do not enjoy that,’ said Eric. ‘Why are all those ducks there, like that? There’s no reason for them to be there. There’s not even a pond or river. It’s just a field. I’m telling you, pal, I’m not happy about it. That’s far too many ducks.’

‘I love you,’ thought Carl. ‘You are a ridiculous human being, and I love you.’

As the path followed the curve of the earthworks, it pitchforked into two fading prongs then died away to lethargic winter-bramble mess and decomposing tree-trunk muddle. Above the two friends, the Iron Age fortification steepened. Did the deer who had originally formed this path – Norman? Roman? – lose heart and decide to throw in the towel at this point? Thinking about the dog, and the falling sun, Carl pressed on, thorns tearing at his flanks, with Eric a few steps behind. Every time he dropped a gear, allowing his companion to catch up, he could hear a small whistling noise coming from Eric’s chest: like, but in a slightly different register to, the other small whistling noise he had recently witnessed on car journeys when Eric became visibly troubled by congested traffic or the senseless actions of his fellow drivers. Carl leapt a fallen tree and, seeing no easy way through directly ahead, began to scale the steep prelapsarian wall to his left. For this exercise, being quite sure there was no other human in sight besides Eric, he took his weight off all fours and rose to his full height, which was his preferred state, particularly where severe gradients were concerned.

Behind him, accommodating the change of direction less easily, Eric remonstrated with piked branches and vines.

‘Ey, do one, you divvy.’

‘Lay off, soft lad, or you’ll get what’s coming.’

‘I paid thirty quid for these here keks, you fuckin’ binhead, and I’m not having the likes of you ruining them.’

‘Everything ok, back there?’ asked Carl.

‘Sound, pal. Don’t you worry about me.’

Those who know Dorset well – those who, like Eric and Carl, have spent many hours deep within its creases, slits and folds – know it is the most deceptive of the West Country counties. It is the taller-than-average broad-shouldered gentleman you meet and think ‘Oh my, look at his freshly cut, neatly parted hair and tailored clothes, he must be enormously civilised – maybe I will accept his invitation to dinner’, whose house you then go to, only to find it is a hole in the ground containing half a chair, a corn dolly and the remnants of an old fire. Driving the top roads, eyes directly ahead, you’d never suspect a place like the one Eric and Carl found themselves in right now existed. Unfarmed, uncoppiced, unmanicured, unpollarded, unconserved, unmaintained, it was as toothy as it was halcyon. It was the place foliage came to live its best unfettered off-grid life, unafraid to be a cunt: a dark spunking of undergrowth where trees did their most clandestine bidding and badgers and foxes and rabbits hid from every soul in Christendom who’d ever wished them ill. Eric found the steep barrier of earth that faced them tough going. Knots of old brambles grabbed and tore at him. Unseen tree trunks punched at his shins. He felt that a spirit not far from the surface of where they trod had been awakened and its one mission was to vanquish him. ‘Will this be the venue, then? The one where I will finally expire?’ he thought, looking up into the latticework of the trees on the rim of the ancient tribal defence point from his position, on his back, on the rapidly crisping damp earth, where he’d been knocked for the third time in as many minutes. ‘Here, in soft southern Tory Wessex? I, who have made my bed in the L8 postcode of Liverpool, and behind a tin mine in the Cornish interior, and in the bit of Nottingham people in Nottingham warned you not to live in, and under the frowning brow of a Welsh mountain, and, for four whole months, opposite a bookies in one of the more antagonistic towns in south Derbyshire?

‘But – hold your horses, pal – what is this miracle, that is now saving me? Why am I now floating above the ground, free of the tawdry attentions of underbrush and sharp bristles? Is this my final ascent to the Good Place? And what will be the verdict when I am there? What will count against me, when all is added up: how many of my blunders and infractions?’

But it was just Carl, hoisting him from his damp place of despair towards the waiting sky.

They were an hour and three minutes late arriving at The Meat Tree’s place, a tall redbrick house, built to last, where barely an inch of interior wall was not covered by fabric, art or bookshelves. This was what the clock on the van’s dashboard informed Carl, who, once night had fallen, relied on devices less romantic than the skies for his timekeeping. Fortunately The Meat Tree, having known Eric for over a decade, had made allowance, substituting “six” for “seven” when emphasising to Eric his deadline for leaving the building. A few acquaintances of Eric’s had distanced themselves from Eric over the years as a result of his apparent antipathy for all notions of punctuality - one even going so far as to arrange an official summit to discuss the problem - but The Meat Tree wasn’t one of them. Possibly the central fact to know about Eric was that Eric was Eric and was always going to be Eric and that was just something you had to accept if you wished to regularly continue to spend time in Eric’s company. In a more general sense, The Meat Tree was also aware how pointless it was to campaign to alter the core ingrained behavioural habits of any man of 67, being almost one himself. He opened the door to his friend with a grin and a fraternal pat on the shoulder which, once he saw the state of Eric’s trousers and footwear, evolved into a restraining arm.

“You know the rule, Inskip,” said the Meat Tree. “Shoes off before you come in. Why not give yourself a good old shake while you’re at it.”

“For fuck’s sake,” said Eric, complying on both fronts. “I feel like a naughty horse. Why don’t you get me to do a little dance while I’m at it? I’m pretty nifty at the Watusi, but it’s been a while.”

From the window of the van, with a subtle smile spreading across his face, Carl watched this scenario, which bore sturdy resemblance to one he’d hypothesised on the way here. He enjoyed visiting The Meat Tree’s house, loved its maximalist ambience of learning and needlepoint warmth, but, not having the luxury of footwear of his own to remove, had decided to stay put, being worried about shitting up Meat Tree’s nice Turkish rugs. He also had a Rosamond Lehmann novel he was keen to get back to, even if that meant clambering over the seats for half a dozen hastily devoured pages in the back of the van.

“That new?” asked a now marginally less soiled Eric, stepping into The Meat Tree’s hallway and pointing to a painting above him at the head of the bare wooden staircase, depicting a lugubrious woman in a hooded black cowl, whose warning eyes appeared to track his every step as he ventured deeper into the building.

“Fairly new,” said The Meat Tree. “I got it in Bridport, off Salford Ricky.”

“Ricky! Bloody hell. You don’t want to get anything from that tottering fiasco. You should have come to see me. I’ve got a tonne of depressing shit like this in the lock-up.”

“Ah, he’s not a bad sort, Rick.”

“I’ve known shadier Mancunians, I will admit. Shite jackets, though. Don’t know how he manages to find so many quite that shite. He must go to Shite Jacket Warehouse or something. So who is she, the bird?”

“Well, the title on it says ‘Welsh Woman’ so I’m deducing from that that she may have been a Welsh woman. I think it’s from the 1800s. Very early 1800s I’d guess, from the Palladian frame. There’s a signature but it’s almost completely faded. Carl not with you today? Tea?”

“He’s in the van, sleeping. We did a long walk. I knackered him out. Don’t think I’ve ever seen him panting that much. Nah, pal. You’re all right. I won’t keep you. I know you’ve got to leg it. So what’s the deal with this place tomorrow?”

“The Meat Tree” was of course not quite what it had said on The Meat Tree’s birth certificate, in 1957, when it had been presented to his soon-to-emigrate parents in Astakos, Greece. The name derived from a misunderstanding by Eric and Carl’s friend Mel, back when Mel and Eric had been briefly a couple. “Who’s Dimitri?” Mel had asked, the first time Eric had referred to his bibliophile acquaintance in a text message to her. “Are you going mental?” asked Eric, who, while aware of Mel’s occasional feathermindedness, was unnerved by this blank spot, since she’d already met Dimitri twice and heard Eric talk about him on dozens of occasions. Later that day, in person, they straightened it out. “Oh, DIMITRI!” said Mel. “So that’s what he’s called. I always thought you were saying ‘The Meat Tree’. I had assumed there was some kind of story behind it but didn’t like to ask. If I’m honest, I did think it was a bit weird.” By assuming the story, Mel - in a thoroughly Mel act of Melness - had made the story, become the story. From that point on, to the weary forbearance of The Meat Tree himself, the name had stuck.

In truth, The Meat Tree didn’t look much at all like a meat tree. What nobody could think, upon scrutinising him for the first time, was “Giant Redwood made of ham”. He weighed a little less than a rich child’s go-kart and stood fractionally over five and a half feet high with wiry grey hair that put people in mind of a brief unnecessary exclamation of alarm, a neat beard and clean hands with smooth clean fingernails and small palms and long fingers. Ideal fingers for gently examining and evaluating rare books, which was how, for the last couple of decades, since being made redundant from his post at a small municipal library on the Somerset Levels, The Meat Tree had earned a living.

What The Meat Tree and Eric had in common was that their jobs involved picking through the clutter and dust of lives, relieving others of what they had realised they couldn’t take with them or what, if those same others were too late in coming to that epiphany, sisters and brothers and children and nephews and nieces and grandchildren did not have the time or inclination to selectively put up for auction. They were the ones who placed it back into circulation, finding a slot for it on the ever-spinning carousel of Lovingly Made Hard-To-Find Old Things That Get Better As They Age. Neither had chosen their profession for its anthropological perks but they enjoyed them almost every day. They heard so many small, intertwining stories, they couldn’t help but become storytellers themselves. They hung around along the seams of life, regularly experiencing truths about its shape and weight that most people rarely did. But that was where their similarities ended. While The Meat Tree’s specialisation was books, Eric dealt in used records, “plus a few other bits and bobs” as he would put it, although the “few other bits and bobs” part had begun to dwindle more recently. The people who bought what The Meat Tree had to offer spoke quietly and with great care, as if wiping every word with a soft cloth before it left their mouth. They complimented one another on their expensive scarves. They circled awkwardly beneath bookshelves in a dance of exemplary manners until finally one of them gave in and reached the shelf first and picked up the very first edition hardback the other one had been trying to hunt down for years and had travelled here, several hundred miles, specifically to find. “Are you sure you don’t mind?” they asked. “No, please, really, be my guest,” they said. “Exquisite endpapers on that,” they said.

Eric’s clientele, by contrast, wore politeness like a thin summer cardigan. Upon entering the building and seeing a box marked “rare cosmic jazz: 1/2 price!”, they relieved themselves of this impractical garment by absentmindedly letting it fall to the floor, where it was soon trampled by shoes discreetly stained with street vomit, piss and last night’s spilt ale. The money that many of them might have been better advised to spend on toiletries they splurged on freakbeat 45s and scarce Afrofunk and post-punk test pressings. Any concept of acceptable elbow room that society had taught them became a distant memory, in sight of their prey. Devoid of daintiness, the dance they performed was that of haggling goats. You could almost hear the clack of locked horns as an agreement was reached. When it wasn’t, the time lag and physical distance between saying “Ok, I’ll leave it in that case, mate” and mumbling “Stingy wanker - he’ll be lucky to be get half that much for something in that condition” was expertly judged, just as it had been so many times before. A few of them were just casually looking for a bit of recorded music to listen to in its most authentic form, but most were lost in a descending mist, striving to fulfil some atavistic hunter-gatherer need, as urgently and single-mindedly as if the survival of their nearest and dearest depended on it. What they generally discovered when they got out of the mist and back to their front rooms was that they owned some more records to add to some shelves that already contained a large number of records.

The beauty of Eric and The Meat Tree existing in independent universes within the same universe was that they could help one another out every now and again with no peril of treading on one another’s toes, no danger of crossing the streams from their proton packs while rounding up their ghosts. Eric read books but felt scant physical attachment to them. When he’d finished them - and, no less frequently, when he hadn’t - he left them, usually much stickier and more dog-eared than when he’d found them, in friends’ bathrooms, hotel rooms, on trains, buses, benches, on the walls above blacktop estuary footpaths. The Meat Tree was a person only lightly shaped by the musical revolutions he’d lived through, not tied to any genre or era, a marginally more than passive consumer of other people’s recommended noise, which is to say he had a Spotify account he sometimes remembered to use, a couple of Beatles LPs and a copy of Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Bookends’ in the loft and just about knew who PJ Harvey was - mainly because, nine years ago, she’d ventured into The Meat Tree’s short-lived physical book shop in Lyme Regis and purchased a hardback about Pagan iconography in the churches of Wessex.

The key that The Meat Tree now placed into Eric’s hand, entrusting him with its safekeeping, would tomorrow open the door to a building more than three times the size of any that either man had ever resided in: an 18th Century manor house containing one of the most flabbergastingly excessive book collections in southern England. The Meat Tree had already done his work in Corndon Manor, over the course of three intense and exhausting visits, separating what he would offer the family of the Manor’s late owner a non-insulting fee for from what would soon be removed by a less highly regarded book dealer and a house clearance company. During the course of his investigations, he had lifted a stray horsehair blanket and spotted two split cardboard boxes, both half-filled with long-playing vinyl. “Of course, I can’t vouch for its condition,” he told Eric. “The place is riddled with damp and probably hosts at least three warring colonies of rats. And what’s in there might just be worthless crap. But maybe there’s some more that I missed. And you really need to see this place - as an experience alone it’s worth the price of the petrol. I swear to you that it’s not quite of this planet. Whatever the case, it’s probably worth a look.” It was always worth a look. That was more than an attitude. For Eric, it was a philosophy to live by. What kind of purveyor of vintage items would he be without it? Probably the kind who no longer purveyed vintage items at all but was living a far less varied and interesting sixtysomething life after retiring from a significantly more beige job.

Carl, now back in the passenger seat after finding himself regretfully unable to focus on Rosamond Lehmann’s 1936 novel The Weather In The Streets, watched his best friend emerge from The Meat Tree’s front garden under the glow of a street light, neglect to reclose the gate then cross the road back towards the van, a spring in his half-limping step. Between his index finger and thumb he held a piece of knotted string attached to a dark brown metal key of comically large dimensions which he dangled theatrically at Carl in the manner of a man who, thanks to his conversational swagger and influence, had secured the use of the honeymoon suite of an exclusive medieval castle hotel for the weekend. Okay good, thought Carl, it looks as if he isn’t going to die just yet.

Ninety minutes earlier, scaling the hard-packed former defence pinnacle of the Durotriges tribe, feeling 76 kilograms of wheezing, thorn-damaged record dealer on his back, he had felt less confident about that.

“Can you just give me a minute or two, pal?” Eric had croaked in a stale scrap of his normal voice, when Carl, having negotiated the worst the hill had to offer, had deposited him on a ledge just under the summit’s shaggy, overhanging rim. Returning to all fours for the final part of the ascent - though it was dusk on a weekday, there was no guarantee that fellow walkers would not be milling around the summit of the hill fort - Carl had sought out a soft spongy patch of grass to stretch out on while he waited, with a good view of the last of the sun dropping over the distant cliffs, and, feeling the cooling grass under his tail and hands, permitted himself to indulge in a brief analysis of the destination he and Eric had reached in life.

It does feel like a destination, he had thought. And not a bad one, at that. Just over the last green shoulder on the left, less than four miles distant, in the narrow cleft of a salt-blasted valley, could be found the cottage they shared: an overstuffed, rented cottage, certainly, but an attractive rented cottage, significantly more idyllic than the majority of places they’d lived together in the past, with a spacious garden, and where they felt reasonably confident in being permitted to stay - and being able to afford to stay - for the foreseeable future. After a little wobble during the nadir of the pandemic, Eric’s business had bounced back to rude health, and beyond. No doubt aided by the sea air, Carl’s coat had never looked in better condition. Clients Eric talked to about the gigs he’d been to in his youth often closed one uncomprehending eye when he cited dates, having mistaken him for a man a decade younger than he was, partly due to his skin and posture but also due to his uncontainable entrepreneurial energy, which Carl had never seen him spark and fizz with more of. Any restrictions regarding their diet were imposed by health concerns, not financial ones. Their domestic environment - although never quite as clean and tidy as Carl would have preferred it to be - was quietly earthy and stylish, filled with the chairs and tables and cookwear Carl (and, to a more distracted, less aesthetically particular extent, Eric) wanted, rather than cheaper stand-in versions of the chairs and tables and cookwear they wanted. They owned six charismatic chickens, none of which attacked their legs when their backs were turned. Their local swimming pool, though a bit chilly for ten months of the year, was pleasingly uncramped, measuring a total of 139 million square miles, and, with a little light trespassing, could be reached on foot in less than eleven minutes. Their life was dominated by Eric’s work but left Carl ample time to follow his passions: needlecraft, reading, Dolly Parton, husbandry, obscure historical facts, snorkelling. They went on holiday, sometimes, but - since there was so little to escape from - didn’t especially feel the need to.

Have I cursed us, in a moment of absentmindedness? Carl had asked himself, as he stretched out on that rapidly cooling grass. Did I break the golden rule of never saying “Things are going really well right now!” because it’s always when you say “Things are going really well right now!” that everything bursts into a giant rolling ball of fire, or at least begins to splinter and crack? If so, at which point must it have been that I let my guard down? Six, seven weeks ago?

That was when he’d first noticed the noise: the one that leaked from Eric’s body in the front of the van when he was dealing with anything even marginally stressful in front of him on the road, the one that Carl tried not to worry about but instinctively wanted to reach over and repair, like a plumber poised with a putty knife in front of a damaged pipe. Then there’d been the forgetting of things that had never previously been forgotten: names of oft-visited places and favourite records and songs and even bands. A map incorrectly read. The year of a record’s pressing, in perhaps the most shockingly uncharacteristical error of all, incorrectly identified. Little incidents, but enough of them for Carl to take notice. And then a moment of larger significance. From his bedroom window Carl had seen an old man in their garden, with an old man’s late autumn posture, taking two packages from the postman at the gate, then dropping the packages, then bending to pick the packages up then standing, then, finally, on the third attempt, achieving success. “Who is that old man, stealing our mail?” Carl had thought, before realising that he was looking at his housemate: looking at him from an angle he’d never looked at him from before, not his usual Carl angle, but perhaps the angle from which others now saw Eric. And then, just a few minutes ago, in that wild place below him, this vulnerability which might have been predominantly comic, even a year ago, but which now, bewilderingly, unbalancingly, wasn’t.

There was a lot Carl knew about himself and a lot he didn’t know. In fact, Carl sometimes wondered if there was any other creature on the whole planet who simultaneously knew so gargantuanly much and little about themselves as Carl knew about Carl. Carl knew that Carl was fundamentally kind and had never intentionally done anything to hurt another living being. Carl knew that Carl had an immense tolerance for spicy food, more immense probably than that of any human, even more immense than Eric’s friend Reg Monk who, it was said, had once eaten all of the hottest curry in the spiciest restaurant in Newcastle Upon Tyne - a curry so hot that the manager’s official policy was that he’d waive the bill on it if anybody was superhuman enough to eat all of it - then ordered it again, polished off every last morsel, then gone home and stunk his house up so much that his wife Jill had moved into her sister’s place for the following four days, taking the kids with her. Carl knew that Carl possessed a capacity to be a more sociable being than he was, and that a whole other strand of happiness would spread from the fulfilment of that capacity, but that circumstances rendered it almost completely unexplorable, and that was fine, because in the grand scheme of life, things could be much worse, and indeed had been. Carl knew that Carl was more intelligent than Eric but knew that did not make him better or more important than Eric. Carl knew he was lucky to live in the age of Wikipedia to a degree approximately equivalent to the degree that he was unlucky to live in the age of a lot of what living in the age where something like Wikipedia was possible brought with it. Carl knew that Carl was sensitive and that life would be less painful if he wasn’t so sensitive but also that he didn’t want to be less sensitive, no way, not in a million trillion years, not for all the spicy food in Thailand. Carl knew that he would like to stand proud and upright in public and walk around on his two stronger back legs and converse with more people than just Eric and his friend Mel and knew that his self-esteem would be greater if he did and knew all the problems this would cause and why it was utterly prohibited by Eric, and by himself. But Carl didn’t know where and when or to whom he’d been born. Carl didn’t know why he was covered from head to toe in fur or why he had a tail or why he had hands - exceptionally clever, dexterous hands, each equipped with two opposable thumbs - or why those hands had a total of 24 fingers and why they were hidden in the folds of what looked like fluffy paws. Carl didn’t know what the official name was for what he was, or if there was one. Carl didn’t know why he was here, right now, only that it was right, or as right as anything ever could be, in this big cosmic accident people called “the galaxy”, with its knock-on effect, “consciousness”.

But within the enigma that Carl was to Carl there were narrow triangles of knowing: they came to him in slivers of phosphorescent light, in a language his brain didn’t speak, but - because that brain was a sophisticated and empathetic one - could roughly translate into noises splashed and rutted with meaning. The triangles frightened him on occasion, especially as he wasn’t totally sure whether they were in his head or in the world or both. Some of them contained images he knew he’d already seen, without knowing where or when. These images made him feel like time didn’t exist, which also unnerved him, because he loved time, loved the way it shaped the landscape, loved the way the sun abided by it, loved what it did to faces and to music and to objects crafted with passion and honesty by hands. The triangles had slowly become larger and more frequent in recent years. And something about that frequency gave him another knowing that he felt physically, coursing innately through him, felt in his face and legs and arms and tail and torso and eyes and all eight of his thumbs: the knowing that he was not destined to be here very long. But he didn’t talk about that or worry about it. It grounded him, in fact, framed his relationship with Eric. It allowed him to find an extra solace, every day, as he observed Eric. The solace that Eric would always be completely Eric - both right now and after Carl was no longer around. It was a given: one of the immutable facts of life. This new, potentially diminished, more vulnerable Eric - furthermore, this new, potentially diminished, more vulnerable Eric in some not too distant future, without Carl there to look out for him - was not part of the plan. Carl had never expected it, pictured it, or allowed for it, and it knocked him sideways. It was a cold thought, colder than the ground he was stretched out on had become since being deserted by the day’s strong, pragmatic sun.