A Short True Life Account Of A Near Death Experience

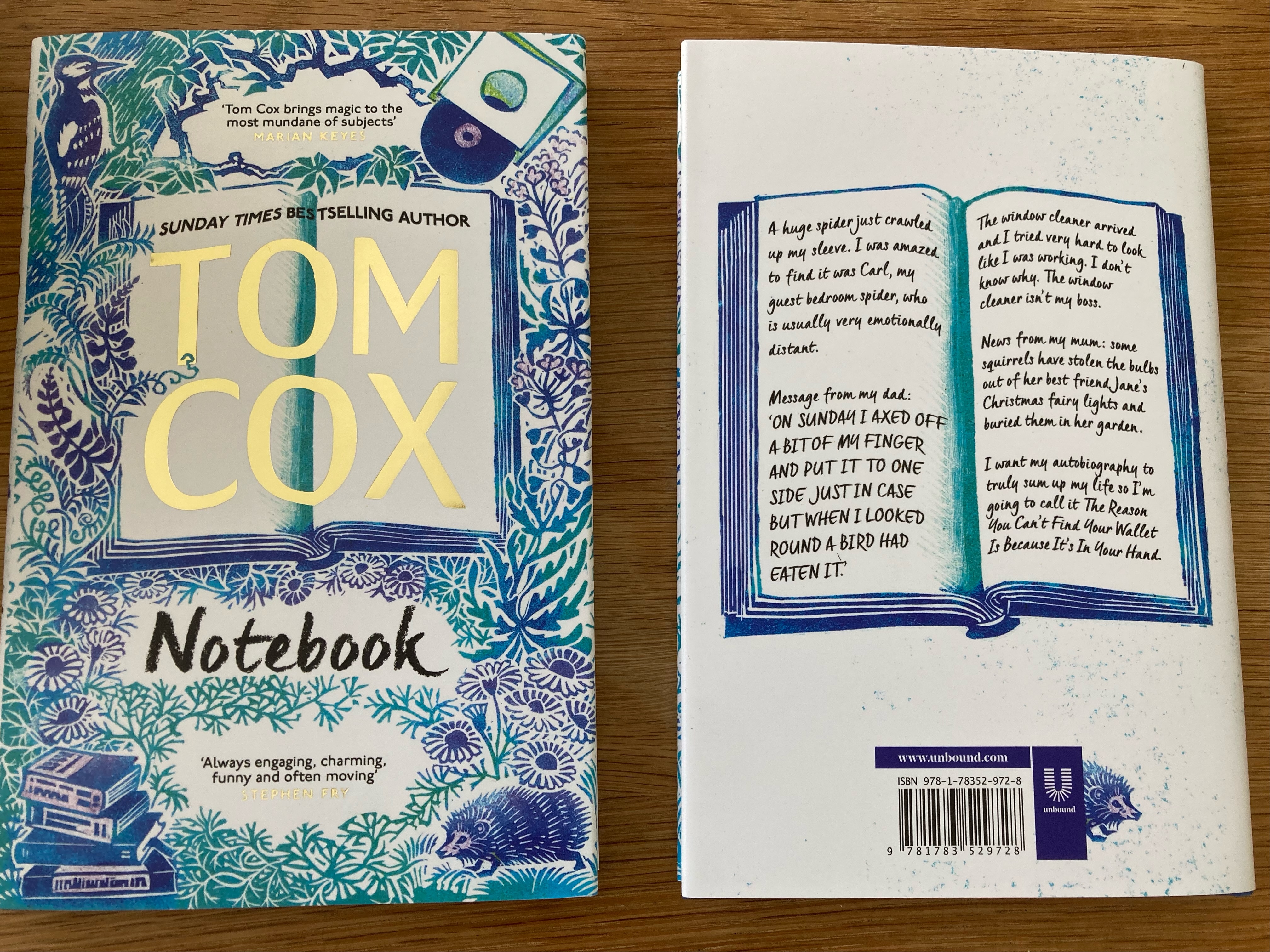

Ok ok so you’ve seen the headline of this piece and you probably want me to get to the point but first, a question: Would you like a free book? As you might know, I’m currently giving away signed hardbacks of both Villager and Notebook to anyone who takes out the paid annual subscription to this page, wherever they happen to be on the planet. My mum Jo has also kindly just given me more original artwork to throw in with these (see the bottom of the page for samples).

Additionally, I recently purchased a large - and I mean large - pile of Notebook hardbacks from my publisher which were left over in the warehouse after the book’s paperback publication (which is of course now the priority for them). While it would be nice to make a little bit of money from these, I am happy to send them out to any free subscriber who wants one (and can’t afford the annual membership fee) for merely the price of p&p. If you wish to give me a little more than that, then great, but if not, no problem. That might sound a little self-sabotaging financially but my feeling is that it’s just nice to get the book out of the spare room and into people’s hands, and if they enjoy it they might become curious to check out the longer books I’ve written recently. Because it’s a slim volume of only 138 pages, postage overseas isn’t quite as brutal as it is elsewhere (around £10 to the US, for example). If you’d like to take me up on the offer just drop me a direct message on the Substack app or an email via the Contact form on my website and let me know which country you’re in. (Also please note that replying to these newsletters on email doesn’t work, as I don’t have a Substack email address.)

I was recently extremely touched to receive this lovely audio recording from the excellent California-based writer of her 89 year-old dad Max - an author himself, and former horse trainer and rodeo cowboy! - reading an excerpt from Notebook about my encounter with Ronald Blythe:

Speaking of audio recordings, there’s one of me reading the below piece here, in case you’d prefer not to read it off a screen, and don’t want to hear some shitty AI version of it:

“How do you get your ideas?” people will inevitably ask you when you write books. The truest answer to this, of course, is “Largely by not being deceased.” The question most authors are most frequently grappling with tends to be less “Where are the ideas?” and more “Where aren’t the ideas?” Personally I often wish there were significantly fewer of the sodding things rattling around in my head since I miss the quiet spells that used to occasionally take place in there when I was younger and more stupid. Yet sometimes you will meet a different set of people who think writing a book is just about seeing some stuff then writing it down. “Note to self,” they picture you mumbling as you walk along the street and notice a leaf on the ground, “make sure book includes a leaf.” They have no concept of the fierce level of competition taking place on a constant, tumultuous basis. For a thing to merit inclusion in a book, it needs to demonstrate its worth. A series of interviews, coursework and exams must be undergone and passed. Failing that, extortion can sometimes serve as a viable alternative. In our garden there currently lives a crow called Frank who, from first light, every day, repeatedly hurls himself loudly at our kitchen window. We feed scraps of food to Frank and sometimes he is especially violent when the spot on the lawn where we leave the food is bare but I know there is more to it than that, that Frank’s appetites stretch beyond just food. Frank wants it all. In fact, it might be accurate to say that it’s Frank’s world, we just live in it. I am, I must admit, quite frightened of Frank. As a result of this fear, I have granted Frank permission to star, as himself, in my new book.

These days I’m not interested in writing a book unless I emerge from it knowing a lot more stuff than when I went in. One of the facts I learned while researching Frank’s part in my new novel is that the farthest from home a carrion crow will fly is generally 12 or 13 miles. Once I’d discovered this, early last week, I felt it was my duty to head out to also research the outer western radius of Fictional Frank, as measured from the fictional cottage where he lives in the novel. On the way, I stopped at the post office which is most local to the house where - along with my partner Ellie, our three cats and Real Frank - I am a tenant. “Where are you off to today?” asked the lady who runs the post office. Being a stickler for accuracy when answering questions about myself, I did think for a moment about saying “Well, in the interests of authenticity and detail I’m off to gather information about the perimeter of the flight path of a fictional corvid, based on a real corvid, for the novel I’ve almost finished writing about a Liverpudlian record dealer who lives behind a Jurassic cliff with a four-legged semi-aquatic speaking creature with triple the combined IQ of Carl Sagan and Sofya Kovalevskaya” but I restrained myself and told her I was on my way to the beach. The sun was pushing through the clouds and I was glad I’d brought my swimming trunks. I parked beside a church and climbed through a wildflower meadow to a clifftop bridleway, then descended a zigzagging path down to the shingle.

As chance would have it, I had written about a fictionalised version of Fictional Frank’s western flying border once before. This was during the summer of 2020, long before I knew about the existence of Real Frank or Fictional Frank, I was on the beach east of Branscombe, halfway through writing Villager, and wondering about the history of the cabins I could see scattered all over the cliffside. I invented a man called Robert Belltower who lived in one of the cabins and who, on the same beach, saved the life of the psychedelic singer-songwriter RJ McKendree. But last week I met a real life human called Nick who has lived in one for almost four decades. He told me about his mother-in-law’s work as a Branscombe Land Girl in the Second World War which had ultimately led him to discover the plot of the cabin, which he prefers to call a “chalet”. He told me about the landslip that had destroyed a couple of the loftier cabins after this spring’s insane rainfall, and about his mate Fluff who is the “Sheriff” of the area, and who, at 80, is still able to run all the way up to the top of the cliff without pausing for breath and will shout at you if you sit on the steps leading down to the beach. Nick also tried to get me into a conversation about the British Royal Family and what a “disgrace” Prince Harry was but I thankfully managed to divert him from that by asking him about the springs that gave the cabins their water supply and the donkeys that used to carry the strawberries and potatoes that had been grown on the cliff back to the village. On the beach, I found a beautiful hagstone, just like I had in 2020.

Before I left, I couldn’t resist scrambling up the cliff to have a closer look at one of the disintegrated cabins, a few hundred feet above me. The first three quarters of the climb was manageable, if a tiny bit dicey, but after that I hit the landslip. In the slightly drier weeks of May’s first half, the red earth had been given time to compact slightly but, as I crawled onto its slick surface, I felt it shift fractionally beneath me and hesitated. Above me, and it, I could see the remains of the cabin, its weather-wrecked innards spilling out into tall nettles and underbrush. I really really wanted a closer look at it.

A thought that goes through my head a lot when I’m coming to the closing stages of writing a book is “I hope I don’t die before I finish this.” I’m not sure precisely why the issue is of such a great concern. After all, were it to happen, I wouldn’t have to experience any of the crippling frustration of not quite finishing a book, what with being dead and all. Nonetheless I decided it would be particularly cruel to perish now, with only around 2500 words - a day and a half’s work, at my recent rate - to go. Yet there was an undeniably poetic element to the circumstances of my potential death. Landslides, cliff falls, the reclaiming of the land by the land - they were all big underlying themes of the book. I even alluded to them in the title. ‘EVERYTHING WILL SWALLOW YOU AUTHOR GETS SWALLOWED BY THE EARTH LESS THAN 48 HOURS BEFORE PUBLISHER’S DEADLINE.’ That sort of headline could do wonders for my Amazon sales ranking, finally push me over the line separating “a bit cult and quite passionately enjoyed by some” to “temporarily edges onto the lower reaches of the New York Times Bestseller List and might be able to even one day purchase a house”. Also, endings are overrated, right? You didn’t read a book just because of its ending. You read it because you liked hanging out with it. I did, anyway. Before I died in a cliff fall and made my first million. 2500 words: that wasn’t much at all. The book was effectively done. Someone close to me would come up with something to round the story off, in my absence.

I backtracked, remembering I wasn’t in fact quite in the afterlife yet. But still my mind wanted to race ahead. Who would inherit my record collection? Would the autopsy reveal that the fall did the final damage, or the suffocation? Would Ellie continue to live in our house or find the sadness too much, move away, eventually finding love again in California with the director of the inferior, bowdlerised film version of the novel? Which of the cats would mourn me most histrionically? I paused, my knees embedded in the steep overturned mud. A rock spun past me, down the cliff, shattering against one of the bigger rocks below. I looked at the precarious remains of the cabin, directly above me. Was that movement I saw, in the building’s crumbled skeleton? In my palm, I clutched the lucky hagstone. Another small rock fell.

I moved backwards, just a few inches, very carefully. Then I moved again, more decisively, scrambled off the landslip and made my way back down the slope.

Frank was waiting for me when I got home. He’d brought a couple of friends. “Fucking hell,” I thought. “They don’t call it a murder of crows for nothing.” I grabbed a bowl of stale tortilla chips that were left over from my birthday the previous day and emptied them onto the lawn. Frank strutted around with one in his beak, as if engaged in the thuggish impersonation of a freakishly large male blackbird. As I wrote the final section of the book that evening and the following morning I would sometimes see him eyeing me through the window from the top of a bank of weeds and wildflowers. Every half hour or so, he hurled himself at the glass, maybe a little more complacently than before. I didn’t see any hard evidence that he had a knife on him but that’s no proof. I suppose it doesn’t matter now. The important point is, by midday the following day, I was all done, and he hadn’t had cause to use it. Everyone was still alive and had ultimately got what they wanted.

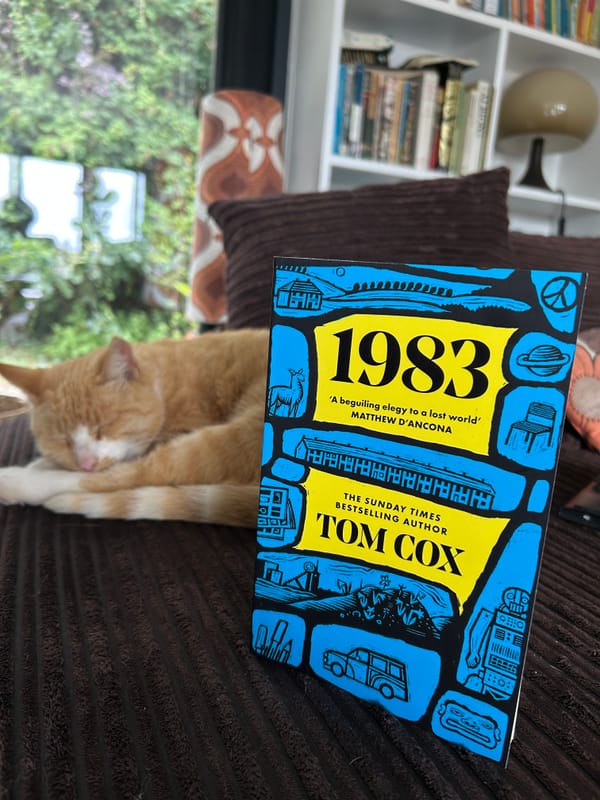

My next novel 1983 is out in August. Everything Will Swallow You will be published in March next year. You can order my first novel Villager with free international delivery here.